Academic Freedom vs "Settled Science"

Academic freedom and vigorous scientific debate should be protected and scientists and researchers need to stay free of intimidation, ostracism and cancelling.

The recent decades have seen a gradual increase of pressure for direct and indirect restrictions of academic freedom. Researchers have pointed out that the influence of corporate interests have clearly increased during the recent decades and in some areas the influence of the corporate industry on academic science is pervasive.

For instance in medicine in the US, influential randomized trials are largely done by and for the benefit of the industry. Meta-analyses and guidelines have become a factory, mostly also serving vested interests. National and federal research funds are funneled almost exclusively to research with little relevance to health outcomes.

It has been highlighted that conflicts of interest in science can threaten public policies and are leaving an increasing mark. Also, politicisation has crept into certain areas of science, which has diminished the real value of scientific research and policies.

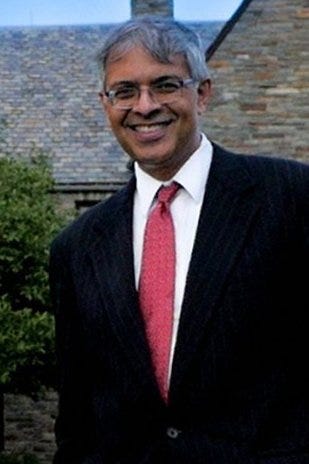

During the recent health crisis 2020-2022, science has been subject to non-scientific factors and influences. John P. A. Ioannidis, one of the highest cited medical scientists and Professor of Medicine at Stanford University,

has defended vigorously academic freedom and has shared in autumn 2022 his observation about the recent Covid-crisis:

"I think my biggest mistake is that I underestimated how much power politics and media and powers outside of science could have on science. I think that I had no clue and no preparation for this invasion of science."

Likewise, Stanford professor Jayanta Bhattacharya has pointed out many examples how academic freedom came under attack, basic academic norms were violated and dissenting voices were deplatformed.

He has stated that:

"Academic freedom matters most in the edge cases when a faculty member or student is pursuing an idea that others at the university find inconvenient or objectionable. If Stanford (University) cannot protect academic freedom in these cases, it cannot protect academic freedom at all."

Slogans like "follow the science" or "settled science" have, in several areas, worked to hinder the real pursuit of scientific inquiry, as references to science have been employed to justify claims with a flimsy evidence-base at best for their support. An example of that are the calls to mandate harsh privacy restrictions and coercive interventions ‘for the greater good’ during the 2020–2022 health crisis. People were told that “science” was a command to be followed, rather than a process for building and testing knowledge.

Several researchers have maintained that creating a false consensus by censoring out certain kinds of information and preventing scientific debates might lead scientists, and thus also policymakers, to succumb to the prevalent paradigm and ignore other, more effective options to cope with the crisis or perhaps even be able to prevent it. Such kind of ‘consensus’ leads to a narrow worldview, which impairs the public’s ability to make informed decisions and erodes public trust in medical science and in public health.

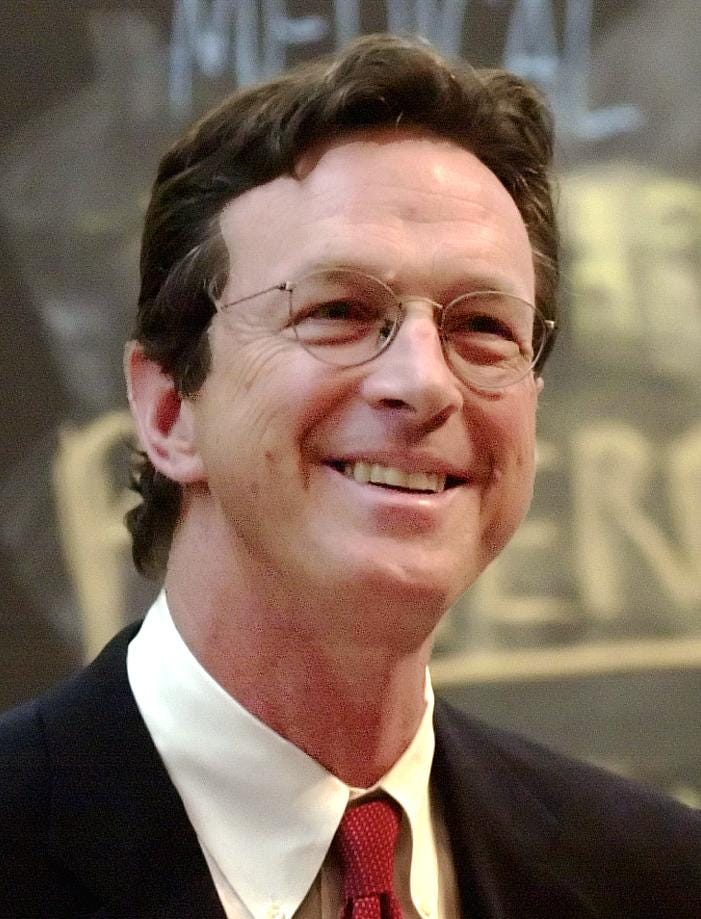

A clear-minded thinker can only agree with the American writer Michael Crichton (1942-2008),

who warned sharply about the rise of the so-called ‘consensus science’ already back in 2003:

"I regard consensus science as an extremely pernicious development that ought to be stopped cold in its tracks. Historically, the claim of consensus has been the first refuge of scoundrels; it is a way to avoid debate by claiming that the matter is already settled. /.../ Let’s be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results. The greatest scientists in history are great precisely because they broke with the consensus. There is no such thing as consensus science. If it’s consensus, it isn’t science. If it’s science, it isn’t consensus. /.../ Finally, I would remind you to notice where the claim of consensus is invoked. Consensus is invoked only in situations where the science is not solid enough. Nobody says the consensus of scientists agrees that E=mc 2. Nobody says the consensus is that the sun is 93 million miles away. It would never occur to anyone to speak that way.”

Scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock (1919-2022)

has noted about the claims of "settled science":

“One thing that being a scientist has taught me is that you can never be certain about anything. You never know the truth. You can only approach it and hope to get a bit nearer to it each time. You iterate towards the truth. You don’t know it.”

Academic research and science is not about reaching any consensus or settlement, which are terms mainly used in political vocabulary, but about avoiding such stagnate and compromise-prone approaches to facts and truth. Instead, science is about offering a method, being under constant improvement, in order to discover and research the vast reality around and inside us impartially and objectively. Scientists are not immune to non-rational dynamics of the herd, especially if consensus is aimed at by the scientific majority. A number of false theories and claims have enjoyed consensus opinion at one time or another even in our recent history.

Academic freedom and vigorous scientific debate should be protected at all costs, which means that academicians and researchers need to stay free of intimidation, ostracism and cancelling, be it inside the scientific community or by the authorities and/or by corporate interests.