China: A Cautionary Tale of Orwellian Order Built on Technology

Sinologist Märt Läänemets talks about how new technology is helping China build a surveillance society and the political-ideological background to the Orwellian way of life there.

Should people in the West feel threatened by China and its system? Given China's developments over the last decade in building a control state and creating a highly effective surveillance society through technology, it would probably be fair to say that Xi Jinping's state should be seen as a cautionary example of how the ones in power strip people of their freedoms if people let them. But aren’t we doing the same in the West?

The problem is particularly acute in the sense that we in Europe seem to be moving towards a similar mindset in various quarters – aiming for more and more surveillance technology and control measures installed under the pretext of our own security. At the beginning of July, for example, the French parliament passed a law giving the police power to locate suspects using their phones or other electronic devices. Under the law, the French police can also directly snoop on suspects by turning on cameras, microphones, and GPS on their phones or other devices.

Or Britain's current debate on whether and under what conditions the police should have access to passport image databases – again, acclaimed for our own security. Passing the law, the police could easily start to compare the photos in a vast database with, for example, those captured by security cameras. At the moment, the database available to the police only contains photos of people who have been arrested in the past. One of the problems is that people have given their photos for the purpose of travel and now the state wants to use them also in criminal proceedings. Advocates of freedoms and privacy rightly point to dangers associated with the use of continuous surveillance and facial recognition systems. It is precisely this that is being implemented very successfully in China's big cities.

A little over two years ago, Estonia also discussed the dangers of a similar database created at the time, aimed at collecting citizens' biometric data – not just passport photos, but fingerprints, eye identifiers, etc as well. One of the major problems identified by legal experts at the time was the fact that when applying for a passport, a person has provided the state a sample of his or her fingerprints, but henceforth the state could use the same, for example, in the context of criminal proceedings or any other control function that it may deem necessary at some point in time. The majority of the parliament was in favour of forming such a database in the end. The decision would provide additional security, argued its supporters.

As a reference, a need to ensure safety on the roads is always made, via measuring the average speed of cars on the roads. Preventing speeding comes at the cost of recording the movements of all the cars using the road, which means that you are constantly monitored as a driver.

The Covid policy, by now forgotten by many, is also a representative example of control measures. Access to services and even to one’s workplace by means of a QR code, a phone call from a state representative after a compulsory test, if it was positive, to remind you to stay indoors, and the police checking compliance with the mask requirement on public transport late at night or forcefully clamping down protests of people who were opposing the rules – I do not want to reminiscence on all the details, but the fact is that such China-like methods of restricting people's freedoms and rights began to be applied throughout the Western world, including in some otherwise democratic countries, with notable zeal.

Communist Chinese influence or the inevitability of a democratic society?

Estonian sinologist Märt Läänemets says we need to keep a close eye on such trends and take the dangers seriously. "Whether it's the direct influence of China or just a trend in our liberal societies, unfortunately, social control and, in a sense, brainwashing, are getting stronger," he says. In addition, according to Läänemets, there is now a lot of intolerance in our society for dissent or for offering an alternative view to the prevailing ideas. He points out how liberal governments are introducing hate speech laws and other policies restricting our basic freedoms.

China is, of course, several steps ahead of us in all this, Läänemets says. According to him, it is true that Xi Jinping's regime has been particularly aggressive in curbing freedoms in China over the past five years. However, he says, to suggest that the country was on a path to freedom from the early 1990s during the rapid economic development would be an oversimplification. This freedom, he says, was primarily linked to entrepreneurship and was kick-started by Deng Xiaoping, who emerged as China's real leader in the late 1970s and began to open up China to Western investment. But this did not mean that he had the plan to democratise the country or give people further political freedoms. His idea was that China would remain a socialist country, but that did not mean that people should be poor. It worked to an extent and the country saw rapid economic development, but on the other hand, by 1989, there was great discontent, which led to protests against economic inequality and eventually to major political protests – the great anti-authoritarian demonstrations at Tiananmen Square in 1989 were attended by hundreds of thousands of people. The protests were drowned in blood and silenced so that today's young Chinese know little about them. However the country's leaders were frightened by them and politically took a course of improving the lives of the Chinese while excluding them from the political process. "The West, of course, went along with it, quickly forgetting the massacre. For the West, China was a huge market in which to invest. It was a very naïve policy on the side of the Western powers, starting with the United States, to think that once we brought a market economy to China, the market economy itself would make the country democratic. The Chinese took advantage of this," Läänemets comments.

In 2001, China was admitted to the World Trade Organisation and this kick-started an even more rapid economic development. But what never arrived, were freedoms and democracy. By now, according to Läänemets, the process has gotten to the point where Chinese leadership has started to reveal their plans quite openly as they feel powerful enough to do that. The Chinese Communist Party feels that now is the time to set its own rules of the game for the world. "So in reality, Xi Jinping has not changed anything. He has now simply turned the cards face up, and we can say that the West is in trouble with a monster of its own making," Läänemets explains.

The reality of Chinese people – constant control

It is clear that materially speaking, the living standards of Chinese people have improved dramatically – no other example of such rapid growth and improvement in living standards can be found anywhere in history. But alongside this, the population has become accustomed to living without freedoms that, until now, have still seemed elementary to us. The proportion of dissidents in the society is very low, notes Läänemets, and people are aware that, for example, political statements against the ruling party will be followed by repressions by the authorities. This does not mean, however, that the Chinese live in some kind of a black box, or that they are completely brainwashed and do not want political freedoms. After all, they have access to the internet, despite all the firewalls and obstacles. To avoid problems, speeches and commentaries critical of the authorities often use figurative language, a roundabout way of saying things, which the Chinese language is well equipped for.

Läänemets adds that surveillance and enforced loyalty to the government did not start with the communist regime, but has been applied in all of China’s previous empires. "It has been said since ancient times that the emperor and the government of the emperor, or the party and the government today, are like a mother and father to the people. The state is like this great family model. And then the saying goes that mum and dad can sometimes be tough, give a beating once in a while, and the children may not be very happy, but mum and dad are still what they are," Läänemets explains.

A society of surveillance is several thousands of years old. "China's first emperor, who ruled over 2,000 years ago, unified China and ruled with quite a heavy hand, imposing strict control over his subjects by dividing the population into so-called units, modelled after the military. The smallest unit was between five and ten families, and they all had to constantly monitor each other and report to the authorities. If one member of such a community or unit made a mistake, the whole family was punished, or in the case of major mistakes, the whole community," says Läänemets. He adds that there have been also freer periods in Chinese history, but once the Communists came into power in 1949, they took over the machinery of control and stepped it up to a level never witnessed even in China. The Western, especially the Soviet communist theory and practice were combined with China's own ancient repressive model of government. Läänemets cites the example of 'neighbourhood committees' that were set up in villages and towns under Mao. These were formed, for example, on the basis of apartment blocks, where people would then watch over each other. Authorised persons had to report all the activities that were going on to the authorities. As there were few telephones, all communication was recorded – whoever called, when did they call, from where, and to whom. There were also restrictions on movement – i.e. you could not go outside your area without a permit from the authorities.

Orwellian technological surveillance system

In this day and age, however, technology has provided unprecedented opportunities to track people. We're not just talking about cameras, but also facial recognition systems, various 'checkpoints' where you need to show QR code permits from your smart phone, right up to really Orwellian drones that flew behind people's windows during the Covid restrictions and informed them to stay at home. This kind of surveillance is probably not ubiquitous in such a big country, says Läänemets, but it is there in the big cities. He cites the example of CCTV cameras, which are commonplace here as well. However, in China, in one of the city centres, he recalls an article he read, there is a camera for every 15 people – “for security reasons”, of course. As people's information and biometric data are collected and the government efficiently employs artificial intelligence, it is in principle possible to identify where each person is and what they are doing at any given time. It is also common practice in that society that anyone who breaks the law or even just disturbs public order will be publicly exposed – in cities, for example, large LED screens are installed to display their faces. "Political confrontation is, of course, the hardest mistake of all, and the Chinese know it. In this respect, perhaps they are even more cautious. But all the other everyday misdemeanours, from crossing the street with a red light to saying bad things to someone in the workplace or picking a fight, are also taken into account. Even unacceptable relations with foreigners, such as communicating on the internet," explains Läänemets, adding that public shaming is also an old practice, although nowadays, in the age of technology, it can be done more effectively.

Continuous monitoring also goes hand in hand with the so-called social credit system, which China has implemented in some places. According to Läänemets, it is a scoring system where points are deducted for each infraction and added for being compliant. Let’s say, for example, that a person has 1000 points. If he or she makes a statement critical of the government, 200 points are deducted. For any minor mistake, the loss is less. But if you do something good, are decent, and help an elderly person cross the road, you can get more points. In general, nothing much may depend on it, but occasionally it can affect a person's life. "For example, if you want a new job or promotion, they'll look at this account. For example, they'll say, 'Look, man, you've only got 300 points left and you want a better job or a pay rise?' No, it doesn't work like that. You get a worse job, we'll reduce your salary. But the other colleague, he's got 2300, he's a good person, we'll promote him," says Läänemets, giving a vivid example. He adds that according to some studies, the Chinese don't really object to the system and see it as a positive thing – it helps people behave better.

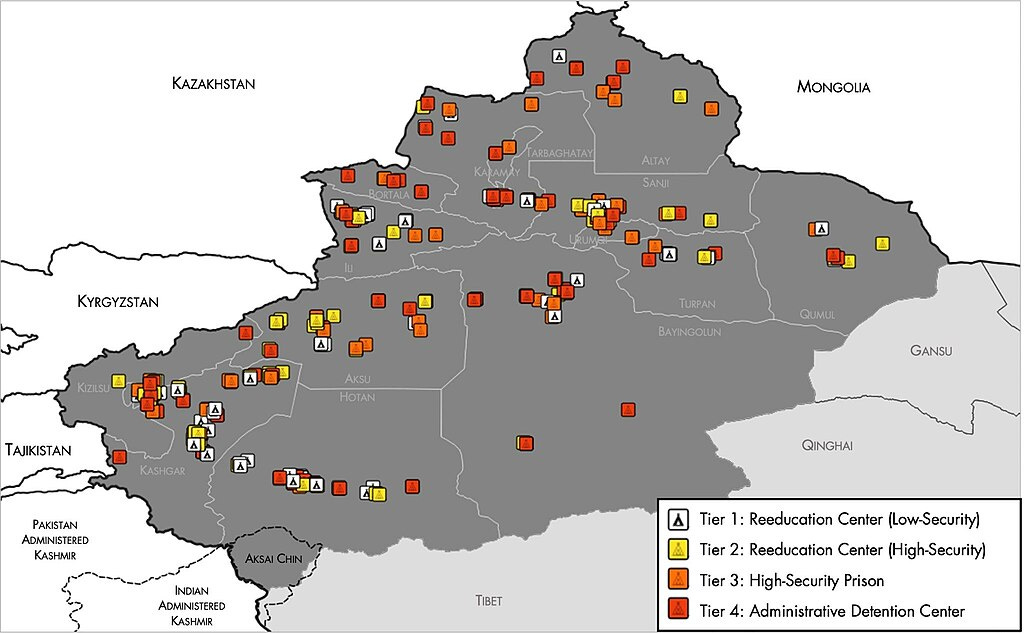

Läänemets specifically highlights regions that are already historically subaltern and critical of central power, such as the autonomous Muslim Uyghur region of Xinjiang province, as well as Buddhist Tibet and Inner Mongolia. There, both repression and surveillance systems are applied in a particularly brutal way with the help of technology. As a result, up to a couple of million Uighurs have been locked up in concentration camps, known as re-education camps, although in recent years the issue has been in the world’s spotlight and the number of such detainees has declined. According to Läänemets, people who have escaped to the West have spoken of both violence and a total surveillance system outside the camps. "To the point that everyone is being watched one by one. There are police stations every few hundred metres, where you are also watched with the 'eye' and at any moment you can be checked if you are a Uighur," Läänemets says. He gives an example that if a person goes to work every day from home along a certain route and then one day goes another way, the authorities have immediate reason to suspect and arrest him. "So in Uyghuristan, under Xi Jinping, particularly harsh methods are now being used to stamp out nationalism and Islam, to make them obedient subjects," Läänemets says, adding that technological progress is providing such mad regimes with dangerous tools.

Covid-crisis as a way of limiting life

As we know, Covid led to particularly severe restrictions being imposed in China for a long time. Läänemets believes that the Chinese authorities feared a pandemic and that the fear of not being able to control the spread of the virus was the reason for severe restrictions. "House doors were welded shut, drones were flying behind the windows, and there are cases of people starving to death at home because they were not allowed to go outside," he says.

However, widespread protests at the end of last year after a fire broke out in an apartment building in the Uyghur capital Urumqi, where people were staying in a so-called Covid quarantine led to the easing of those restrictions. The protests started because people could not get out of a building when the fire started and at least 10 people, and according to other reports dozens, were killed. Demands at the demonstrations also became political at times, and the authorities eventually began to fear them more than the virus. As a result, most of the Covid restrictions were abruptly abandoned, even though only a few weeks earlier it had been confirmed at the highest level that no easing was scheduled before the virus was completely suppressed. The policy change immediately led to a surge in the number of cases, but by now the statistics were no longer published, so it seemed as if there were no consequences. However, it was also very easy to use technology to track protesters and deal with them. "Mobile phone positioning was used to track down, one by one, anyone who was where they shouldn't have been during the demonstrations, and that's why China was so quick to crack down and shut down the demonstrations," Läänemets explains. Läänemets adds that on the one hand, the pandemic was a challenge for the Chinese authorities, but on the other, it was an opportunity to impose restrictions and avoid unrest. However, when unrest did break out, they quickly changed course and contained it.

“We are in a rather bleak situation in terms of freedoms”

However, dealing with Covid by such inhumane restrictions was propagated in the West as a determination to fight the virus on the part of Chinese people, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. The Chinese themselves tried to push this narrative to show that the West could not cope with the situation. "The propaganda was pretty hard. The propaganda was that you see, the West is down in the dumps, they can't control the pandemic. But look, we're much more effective," Läänemets says, adding that it obviously had an impact on us. On the one hand, we saw that in China they were still going completely overboard with welding the doors of apartment buildings shut, but on the other, implementations of lockdown policies and coercive measures soon began here as well. It was clear that something had to be done about the spread of the virus, but the use of such Chinese-style methods in the West was unexpected. "Obviously, government control is stronger after Covid than it was before. Just as after 2001 restrictions were immediately imposed under the guise of fighting terrorism, and on the one hand justifiably so, but at the same time, the same restrictions are still in place today – for example, strict controls at airports, border controls, and so on. The question arises: hasn't the screw been tightened too much?" Läänemets discusses. He cites the example of Sweden, which was one of the few countries that did not go for China-like methods during the pandemic and came through it better than many others.

Perhaps, to sum it up, Läänemets says, such developments towards authoritarianism in democratic societies need to be closely monitored so that we do not find ourselves in a China-like state at some point in the future. "All sorts of organisations and think-tanks that study freedoms also claim that in the last five or even ten years, the onslaught of authoritarianism has accelerated and that there are fewer free countries and societies in the world today. So we are in a rather bleak situation in terms of our freedoms," he notes. So, according to Läänemets, there is no certainty at all that the world will not start to converge towards China, and that is why, he says, we need to be vigilant. "If this kind of creeping control and intolerance deepens in our liberal societies, leading to the strengthening of authoritarian techniques, we could one day end up in an Orwellian world," he says. Free people should not simply make note of new restrictions, but should speak out against them and protest if necessary, Läänemets finds. “This is the only effective method against the so-called sinification," he adds. "Each of us is responsible.”