Claude Monet's Green Revolution

The problem with many of the green policies is their actual disregard for nature.

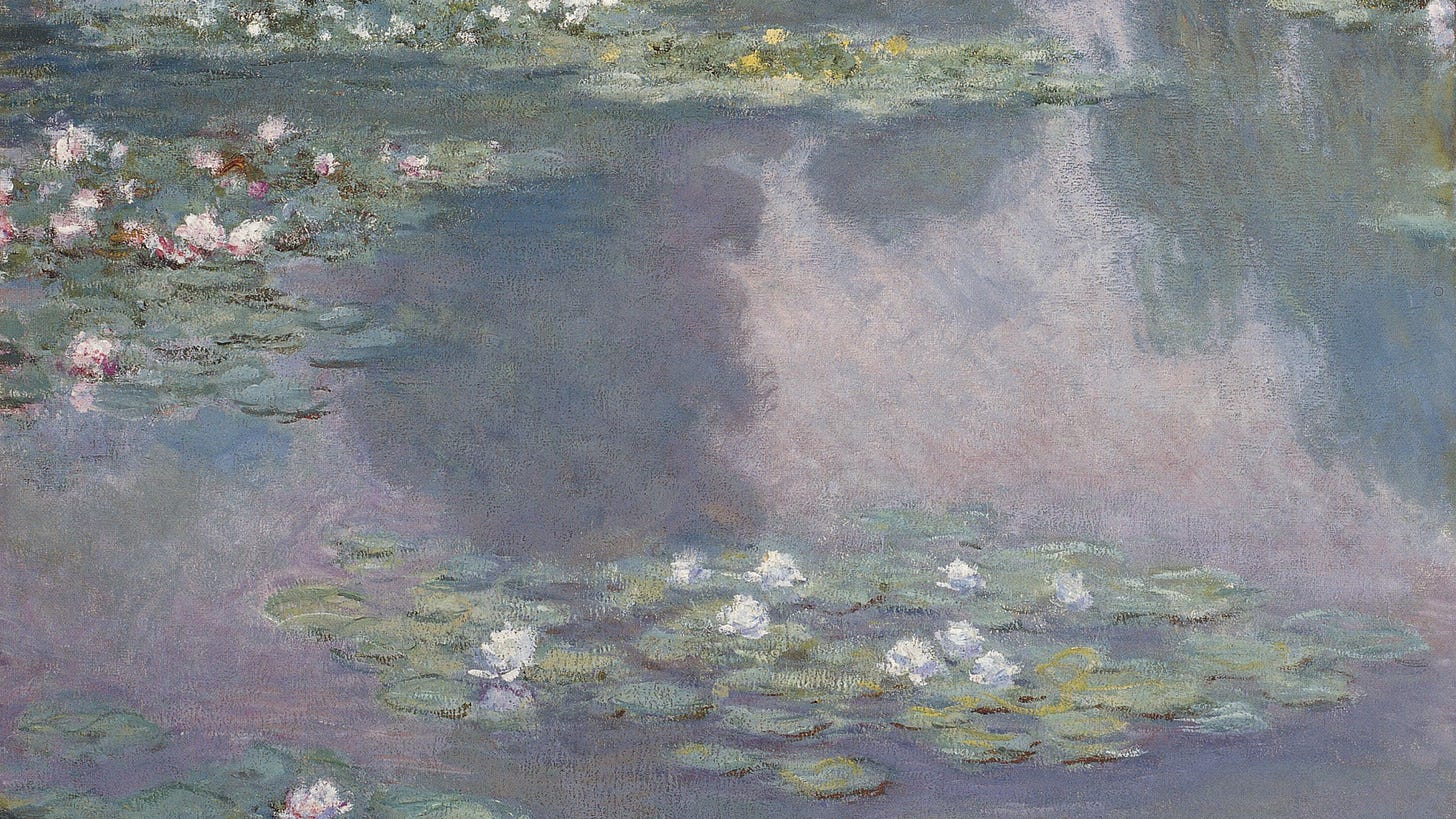

One of the greatest experiences of art in my life was visiting Zürich Kunsthaus back in 2005 for a temporary exhibition of Claude Monet’s garden paintings. Not only did the show startle me with a deep realization about the power of the originals against any reprints, but it also made the painter’s personal relationship with nature very tangible and near. Art has seldom had a similar impact on me again, and among other impressions, it made me rethink my own relationship with my little garden at the time.

Claude Monet (1840–1926), the famous French Impressionist painter, first moved to his future house and garden in Giverny outside of Paris in the year 1883. The move was due to financial difficulties that made Paris too expensive for him to live in, but it also reflected the artist’s growing tiredness of the city. He wanted to be alone, and more importantly, to work alone, without the distractions of other artists and critics, and the city’s bustling activity and noise. Seven years later he managed to purchase the Giverny house he had first rented and he began developing its garden in a number of ways so as to serve as source material for his paintings. Perhaps the most famous move in this process was establishing the ponds for growing water lilies that later found expression on his large panels, most of them now displayed at Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. It was in his garden and around it that Monet eventually produced many of his most famous, revolutionary works.

Even though Monet designed the garden very much according to his artistic needs – considering where the light fell on a particular time of the day, or planting flowers that would provide him the desired palette of colours – the garden carried great spiritual meaning for him as well. The garden was in fact a mixture of a design and wilderness. Monet has, for example, remarked how, for him, “it is essential to think only about nature; it is by dint of observation and by reflection that you make discoveries”, or that for him the garden was “not a meadow, but a virgin forest of flowers”.

He has also said that what he was looking for, and what he tried to express in his work, was the relation – this was something more than admiring nature as an artifact or even more than perceiving oneself to be part of the surroundings. Being in nature was an act of communication, and communion, it was something deeply personal and telling. “Don’t you find that one does better when alone with nature? I am myself convinced of it,” said Monet.

What is green?

I’ll jump now more than a hundred years ahead and to a different continent – I will share with you two sights I came across upon my recent visit to India. The point is not that it’s India though – the same thing could, to varying degrees, apply to many other places in the world. I won’t disclose the exact location of these pictures, but will say they were taken in one of the state capitals and – which is a relevant point – a mere couple hundred metres from each other.

Is there are a correlation between the two? Could one be said to be the cause and the other a solution? Or is the point rather that there is no correlation? Personally I saw them as a graphic example of why I have found it very hard to believe in the green turnaround by the so-called green policies of today, or by those ‘green technologies’ depicted on the wall.

For me the greatest stumble of many of the so-called green policies is their actual disregard for nature. One has to look very hard to find anyone in the policy-making business that would have given an explanation of what nature means for them, or perhaps recounted some personal stories about it or dwelled on its personal importance. Even though the new policies are often enough presented to the public as ‘saving the planet’, they keep treating nature rather the same as many other policies before them: as a commodity, as a resource for exploitation. How the endless fields of solar panels or wind farms will affect our emotional and psychological relationship with the surroundings, for example, is hence a question that is hardly ever asked.

The question of their effect on wildlife is sometimes cautiously brushed upon, but usually avoided as well, for there is no good answer. And here lies the irony: we seem to admit, by our relative silence on the matter, that we don’t understand what nature is, or what our deeper relation to it is, and what we are saving is thereby not really the planet and its diversity, but ‘climate’ almost as an entity of its own. It follows almost logically then that many of the ‘green policies’ actually promote being further removed from nature, suggesting ‘optimised’ urban living instead of following a personal connection with nature as a cause to preserve it.

Indeed, my impression is that much of the ‘green’ discourse goes on under the illusion that the raw materials for windmills, electric cars or batteries appear out of nowhere and leave no footprint by themselves. And it also seems to presume that these technologies will either last forever or else just dissolve at some point with no further effect. For wouldn’t that be the true meaning of ‘net zero’? And on top of that, as I said, we somehow appear to have the foresight – despite the growing evidence to the contrary – that the change will bring no collateral damage on nature itself, be it in the form of habitat loss or potentially declining biodiversity. Aren’t we thus chasing an illusion, one can wonder, or if believing people like Monet, ask, aren’t we replacing the real issue – our loss of connection with the natural world – with a mechanistic pursuit of finding new ways to lord over it. And perhaps wilfully so?

Dependency as authoritarianism

“Your mistake is to try to reduce the world to your own dimensions,” Monet once wrote to his friend Georges Clemenceau. For Monet, art required liberty and freedom, and a gaze beyond the obvious. He opposed his predecessor Realist generation, with the likes of Gustave Courbet, who had acquired a reputation for left-wing political militancy in seeking freedom by depictive social ‘truth’. Monet wanted to go deeper. “I would like to paint the way a bird sings,” he said of his creative freedom. What is the opposite of freedom, I have sometimes wondered, with those statements in mind.

In many cases, I think, the opposite of freedom is not imprisonment – it is dependence. It is very hard to maintain free choice, if one’s day-to-day existence depends on a system which is completely beyond one’s control. In fact, the first strategy of totalitarianism isn’t usually to imprison. Rather, it is to make people dependent on the totalitarian authority or the state as much as possible, for once they are materially dependent on it, only few will retain the courage to step up against the authority at one’s peril. I don’t want to thereby make any far-reaching claims about the covert intentions of today’s green policies, or to speculate about the power grab behind them, but it is hard to deny that at least some of those policies and strategies do carry a flair of authoritarian tendencies.

If land becomes too expensive for people to own, one becomes dependent on others to have a place to live. If moving around becomes too expensive to afford, one becomes dependent on his or her own immediate setup to survive – more so, if by a moral argument, travelling or driving is discouraged to begin with. If growing food naturally becomes so expensive that not all can afford it, be it for the high price of land or banned fertilisers, or other similar pursuits, and artificially or semi-artificially manufactured produce is offered as replacement, one is immediately dependent on select producers for his sustenance. And once everyone lives in a city where all your necessities need to be fulfilled within a 15-minute radius, away from nature, it will be very simple to divert the populace to control, should something in that 15-minute structure fail.

It is natural that one cares about things with which one has a strong personal relationship. The garden mattered to Monet because it was something more than a material resource, far more than a commodity. A parent cares for the child not just because the child is her or his own, but because they have built a relationship with each other. It is of no small meaning or consequence then that, by today, more people on the planet are living in urban rather than rural settings, and among those, a greater number is likely to reside in the multimillion metropolises of the world than in the scattered leafy townlets and suburbs. And it is clear that the more we detach ourselves from nature, the less we will actually perceive its relevance.

Monet’s universal message

Why Monet’s garden paintings have stayed with me and made such an impression on me, I believe, is largely to do with his personal attachment to his subject matter. His paintings revolutionised not only art, laying ground for the later school of abstract painting, but also the relationship between an artist and his object. His work has inspired generations of people to look differently on art and nature, and as a small testament of that, his gardens at Giverny are still eagerly visited by art and nature lovers alike. And as for his paintings, James H. Rubin writes, in his aptly called piece Saving the World, for the National Endowment for the Humanities, “Water Lilies still speak so universally that long lines of people from around the world, as well as locals who return time and again, consider them worth experiencing.”

Any truthful turnaround towards a greener or less wasteful planet needs to start from the ‘greening’ of our minds. Nothing can replace a personal touch, a personal experience of nature. Most of all, it is the children who need to have these experiences. Of course, cities can be green as well, and need to be – we won’t be going back to being commonly rural as mankind anyways – but it takes a lot of conscious attention and planning to make it work. Much like Monet’s gardens that were useful, and yet wild. Otherwise, I’m afraid, the reality of the two photos at the start will remain a long-standing reality. We will proudly beat our chest about how moral and capable we are, and what command we have over climate and nature – not quite unlike the Soviet ‘scientists’ who were proudly turning rivers backwards and trying to grow citruses in the Arctic – while spilling our waste unto the rivulets and meadows without much notice.

“On fine days like those we’ve had recently, I am in raptures at the wonders of nature,” Monet once said. His green revolution thus begun from nothing less than (re-)discovering that sense of wonder. And I very much wish we could finally do the same. There’s this anecdote of two people talking. “What will the future bring?” asks one of them. “I think it is going to bring flowers,” the other replies. “Why is that?” wonders the first. “Because I’m sowing them,” says the other.

[References: Sagner-Düchting, Karin. Monet at Giverny. Prestel Verlag, 1994. / Holmes, Caroline. Monet at Giverny. Cassell & Co, 2001.]