Hate Speech in Finland: Päivi and the Bible

While the usual punishable hate speech case in Finland involves comments about immigrants on social media, Finnish ex-minister Päivi Räsänen's Bible case is different.

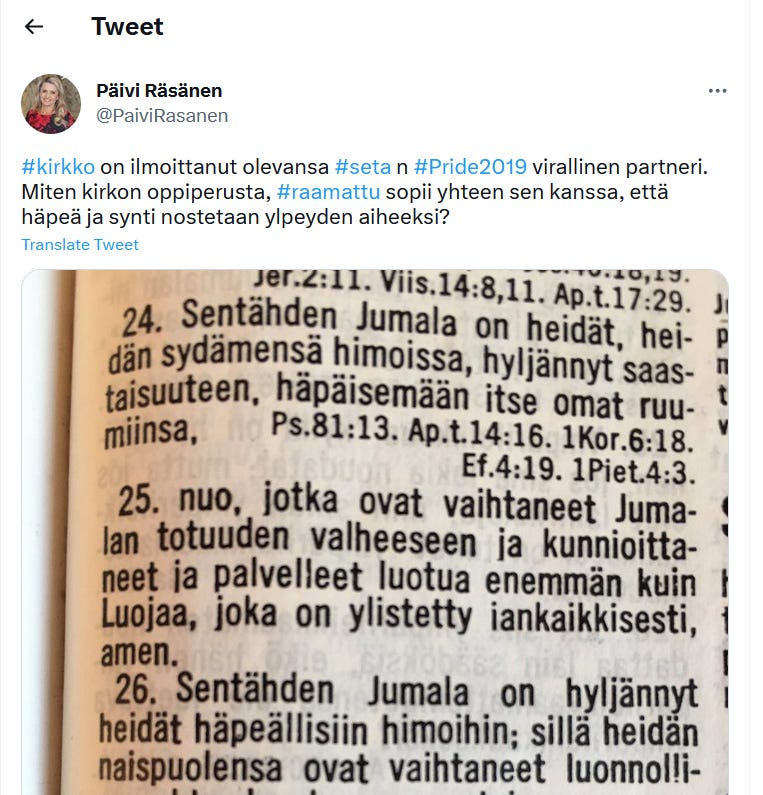

On 17 June 2019, Päivi Räsänen, a member of the Finnish Parliament, made a post on her Twitter account that led to a criminal case against her. On 24 June of the same year, the week-long LGBT festival Helsinki Pride 2019 was about to begin in Helsinki, the capital of Finland. Räsänen is a religious person and has publicly stated for decades that she considers homosexual relationships to be a sin. In her post, however, Räsänen did not directly criticise the Pride festival, but the Finnish Lutheran Church, of which she is a member. In fact, the church had announced its participation in the event. "How can the church’s doctrinal foundation, the Bible, be compatible with the lifting up of shame and sin as a subject of pride ?" she asked. Underneath, she put a photo extract from Paul's letter to the Romans from the New Testament, where in verses 24-27, homosexual intercourse is called unnatural, a dishonouring of the flesh and a substitution of God's truth for falsehood. This post started a hate speech trial that has still not been resolved, almost four years later.

“Hate speech” can land you in jail

Of course, Räsänen is not an isolated case amongst the hate speech investigations in Finland. In last September, for example, the South Karelia District Court fined a 46-year-old man 30 days’ pay on the charge of inciting hatred against a group of people on Facebook, which, given the man's income, amounted to €1,600. The man had posted two comments on his Facebook page which, according to the court, contained prejudice against asylum seekers, insults and threats of violence. The comments could be seen by around 200 of the man's Facebook friends.

While more than 90% of similar cases have so far been punished with a fine, the accused could also be sentenced to prison. In August 2021, a man who discussed the killing of immigrants on his friend's Facebook page in the hope that the violence would drive them out of Finland was given a 30-day suspended prison sentence. The court also found that he had made derogatory remarks about foreigners.

Immigrant-related comments and statements are the bulk of "hate speech" cases in Finland. According to the Finnish police, 1,026 hate crimes were reported in 2021, 20% more than in 2020. In the last decade, the highest number of hate crime reports to the police was in the year 2015 – 1250. Last year, the majority of such reports were cases of verbal insults, threats and harassment, with nearly 70% based on ethnic origin. However, incitement to hatred was on the decline in 2021, according to the report, with 42% fewer reports that year than in 2020.

The Finns Party members "traditionally" on trial

It has become something of a tradition that, because of statements made about immigrants or Muslims, some of Finland's conservative-national wing politicians from the Finns Party end up investigated and are fined in court. The former leader of the Finns, Jussi Halla-aho, received a final ruling from the Finnish Supreme Court in 2012 for his 2008 blog posts as a fine of 50 days’ pay. He had likened Islam to paedophilia and said that Somalis are predisposed to stealing and living on aid.

Former member of the the Finns Party, Olli Sademies posted on Facebook in 2015 that immigrants from Africa should forcibly be sterilised, describing them as beggars and the like. For this he was convicted in court and fined 50 days’ pay.

In 2016, after an Islamist terrorist attack in Nice, France, when an attacker rammed a truck into the crowd, the Finns Party member Teuvo Hakkarainen wrote "anti-Muslim comments" on Facebook. He was fined €1,160 for this.

Sebastian Tynkkynen, the former leader of the Finns Party youth group, was also convicted of hate speech. He was fined more than €4,000 for posting a photo of terrorists on Facebook with the message that said "they all worship Allah".

In June 2020, however, the Parliament voted against waiving the immunity of Juha Mäenpää, a member of the Finns. Mäenpää had referred to asylum seekers as an "invasive species" in a speech in parliament, and the prosecutor's office wanted to open criminal proceedings on this basis.

In February last year, however, Jyrki Åland, a member of the Finns Party, was fined €1,200 by the court. In a video posted on Facebook in 2019, he made remarks towards taxi drivers with an immigrant background, threatening them with violence, according to the court, and in a video posted on YouTube in 2021 he expressed hope that immigrants living in the Varissuo district of Turku would die.

However, in the case of Hussein al-Taee, a Social Democrat member of the parliament, in 2021, the state prosecutor general ruled that no hate speech investigation would be launched. Between 2011 and 2016, al-Taee had made four posts on his Facebook account. In one of them, al-Taee implied that it is a Jewish trait to exploit others in their greed. The prosecutor justified the dismissal of the case on the grounds that al-Taee had deleted the posts himself and that the offences were already expired.

Authorities are concerned about "hate speech"

Of course, some of the politicians' statements can be considered nasty, but what is there to gain for the society when the police and courts consistently deal with someone's social media posts? Would it really be better if politicians and society as a whole started censoring their own thoughts in advance? When someone is literally threatened with violence and there is fear that these threats will be carried out, it is clear to everyone that society must be protected from such people. But the question here is rather how far can society, through self-censorship and threats of punishment, narrow the boundaries of freedom of expression so that 'hate and hatred' are not incited and no one feels 'offended' any more?

Finnish authorities and officials have been repeating it for years that the situation in the country is bad in terms of the spread of "hate speech". The Finnish Ministry of Justice commissioned a study in 2020 to examine the state of "hate speech" in Finnish-language online communities. The result presented showed that in a two-month period – the survey was carried out in September and October of 2020 – around 300,000 hate speech incidents were identified. The study's authors explained that most of the findings came from smaller social networking platforms and forums.

The way of hate speech being supposedly a big problem was echoed by the Finnish police chief Seppo Kolehmainen in early 2017. The number of reports of hate crime had increased, but this was only the tip of the iceberg, he said, admitting that he had also encountered hate speech but had not reported it to the police. He added that he might behave differently next time, and encouraged reporting all incidents.

In March of the same year, the police also launched an online anti-hate speech unit and called on people to report hate speech.

In the autumn of 2017, Raija Toiviainen, the then newly appointed Prosecutor General of Finland, was also concerned about the rise in hate speech incidents, particularly those involving racism. "We have many social grievances and we have to be able to speak openly about them and use strong language, if necessary, but it is unacceptable for someone to threaten, slander or insult a certain segment of society, and in this way, offend people's human dignity," she said.

"Hate speech" prosecuted as a war crime

The prosecution of hate speech cases in Finland depends primarily on the Prosecutor General, as the Finnish Penal Code deals with "agitation against a group of the population" under the chapter on war crimes. The specific paragraph states: “A person who makes available to the public or otherwise disseminates among the public or keeps available to the public information, an opinion or another message where a certain group is threatened, defamed or insulted on the basis of its race, colour, birth, national or ethnic origin, religion or belief, sexual orientation or disability or on another comparable basis, shall be sentenced for agitation against a population group to a fine or to imprisonment for at most two years.”

The provision was adopted in this form in 2010, and compared to the previous version, the groups to be protected were clearly specified, i.e. sexual orientation was explicitly mentioned as a criterion for protection. This is, again, relevant to Räsänen’s case.

The Räsänen case is different

Räsänen's case differs from her Finns Party colleagues’ more usual self-expressions about immigrants and terrorists on their social media. Räsänen is a politician with long experience. She was first elected to the Finnish parliament in 1995. From 2004 to 2015, she led the Christian Democrats and from 2011 to 2015 she was the country's Minister of the Interior. She is a Christian and an opponent of gay marriage. Gender-neutral marriages were legalised in Finland in 2017, with the Cohabitation Act having been in force since 2002. This means that the debate about what constitutes a marriage has also been going on in Finnish society for years. In 2004, the Finnish Lutheran Church Foundation published a booklet defending traditional marriage, written by Räsänen.

Unexpectedly for Räsänen and Bishop Juhana Pohjola, who asked her to write the text and was responsible for its publication, the book became a subject of legal investigation. Pohjola was also charged. In February 2020, as part of a preliminary investigation, he was interrogated for five hours by the police in view of that leaflet.

In addition, Räsänen was charged for speaking on the topic in a radio programme of the public broadcaster YLE. According to the Prosecutor General, all of the statements made by Räsänen were degrading and discriminatory towards homosexual people and violated their equality and dignity. Therefore, they crossed the boundaries of freedom of expression and freedom of religion and could incite intolerance, contempt and hatred. Räsänen replied that, in principle, the question was whether or not it was permissible to talk about Biblical teachings and Christianity in Finland in the future.

At the end of March last year, Räsänen and Pohjola were acquitted by the Helsinki District Court. The prosecution appealed the decision and the case will be heard by the Helsinki Court of Appeal in August. Räsänen herself says she is calmly looking forward to the continuation of the process and confirms her willingness to appeal to the European Court of Human Rights, if necessary. For a more in-depth look at Räsänen's assessment of the ongoing process, see her interview.