Hate Speech Law in Germany: Freedom of Expression Is Being Clamped Down On With Early Morning Police Raids On Homes

Germany is trampling down free speech at such a rate that Russia and Belarus are looking to them as models.

Police raids to the homes of online commentators have become a new routine in Germany, being ever more frequent. Last November, a total of 91 police operations was carried out in 14 Länder on a single campaign day. In the state of Hesse, prosecutors say they opened criminal investigations on three women and six men, aged between 17 and 72. Suspects were accused of online incitement to hatred, defamation and insult. Germany's Minister of the Interior Nancy Faeser said crimes committed on social media, social networking apps and internet forums were “a fertile ground for extremist violence”. "We need to draw clear lines here and get the culprits out of their supposed anonymity," she told AP. German police say more than 2,000 politically motivated crimes committed online are recorded each year, but they estimate the actual number could be higher – many "illegal postings" go unreported for the police or are made in closed groups. Police raids have been carried out in combating such speech, however, already since 2016.

What does this kind of policing mean from an individual's point of view? A similar large-scale nationwide crackdown on "hate speech offenders" in Germany was described some time ago by The New York Times (NYT). In March last year, there was a knock on the door of a home in north-west Germany, which was opened by a young man in his underwear. Police officers asked for his father, who was accused of violating online hate speech, insult and misinformation laws. The 51-year-old man had shared a picture on Facebook of German Green Party politician Margarete Bause who was quoted in the picture, in defence of immigrants, "The fact that someone rapes, robs or is a serious criminal is no reason for deportation." While Bause is a warmly pro-immigration politician, she hasn’t actually said anything exactly like that. And it was the sharing of such a false quote that brought the police to the home of this man and carried out a search for about half an hour, confiscating a laptop and tablet as evidence. Police officers carried out similar operations in about a hundred homes across Germany that day. "We are making it clear that anyone who posts hate messages must expect the police to be at the front door afterwards," said Holger Münch, head of the Federal Criminal Police Office, commenting on the raid.

Police raids with TV cameras

Since 2018, police and prosecutors in Germany have dealt with more than 8,500 cases and more than 1,000 people have been formally charged and punished. Penalties can be imposed even if the person making a social media post does not know the post contains a lie – e.g., a man can say he did not know the quote was false when he shared the photo of a politician, but this is irrelevant. He still faces an initial warning fine of up to €1,400.

People's online comments are monitored by special units in Germany. NYT describes the work of a unit set up in Göttingen in Lower Saxony in 2020, where six investigators are the most "prolific" in the country. In 2021, they dealt with 566 cases of online hate speech, 28% of which ended in fines or other penalties. In Lower Saxony, home search raids are carried out several times each month, often involving the local TV camera crew. If people are not willing to voluntarily reveal the contents of their phones and other devices and do not share their passwords, they are sent to a lab run by the federal government and decrypted using special software. A lot of time is spent by hate crime investigators in finding out who is making posts under anonymous accounts.

There are different types of cases that are dealt with and punished. NYT article gives several examples. One of them is the case of a female political activist who asked the police to help as her political opponents had posted her home address online, which is an understandable appeal – the woman may have feared harassment or even something more sinister, and the case should have been investigated to be sure.

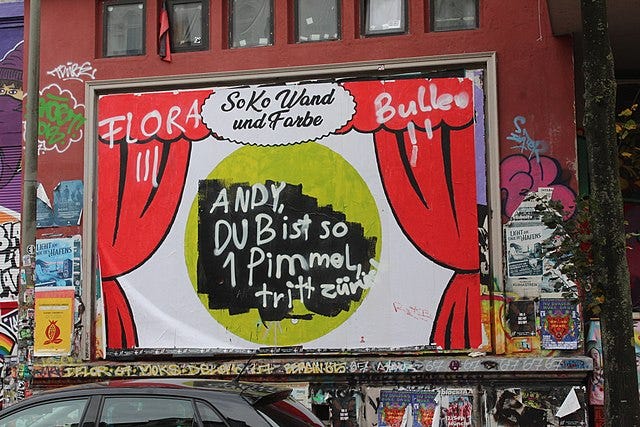

Offended journalist and the Pimmelgate

However, the problem is that, far beyond the nature of this isolated incident, the police are using their special units to investigate “insults”, to assess “false information” or simply deal with witty jokes online. For example, in Göttingen, an artist was fined €10 000 for insulting immigrants from Turkey online.

In 2021, Christian Endt, a Berlin journalist who had been badmouthed in online circles for his coverage of the Covid issue, filed a hate crime complaint with the public prosecutor's office – a Twitter user had called him an idiot and mentally ill person. The "perpetrator" was identified and fined €1000. "I was not even sure if what this guy wrote was a crime or not," Endt himself commented. "In the end, I’m happy they did something about it and this person got a signal that there are some limits on free speech," he added.

Last June, a 49-year-old man was on trial in Kassel, central Germany, for stating on Facebook that Christian Democrat politician Walter Lübcke, who was murdered in Germany in 2019, "was himself to blame”. Lübcke had been a supporter of the then chancellor of Angela Merkel's immigration policy, and a video had been circulating online since 2015 in which he said that those who did not support accepting refugees should move out of Germany themselves. In June 2019, he was murdered on the stairs of his home by far-right extremist Stephan Ernst. The man who commented on the sad event on Facebook said in court that his comment was taken out of context. He had in fact been talking about the fact that Lübcke himself had refused police protection, and in the same comment he had also expressed his condolences to the family. He added that he wouldn’t hesitate to re-post the same comment as it would in any case fall under freedom of expression in a free democratic country. The judge didn't think so – he was fined €2,400.

One of the most absurd cases of the police showing their power to curb freedom of expression, is the so-called "penis scandal", or Pimmelgate in German (Pimmel is German for penis). In September 2021, six police officers searched the apartment of a man in Hamburg at six in the morning who had called a local politician Andy Grote “a penis” on Twitter three months earlier. Grote, who as Hamburg's interior minister, was the enforcer of local Covid restrictions and criticised people partying in late May 2021. He had called them arrogant and their behaviour stupid. At the same time, he himself had attended a party during the 2020 Covid restrictions, and when the fact became public, it caused a political uproar. The penis-posting was made in this context and in response to Grote's statement, and it said: 'du bist so 1 Pimmel' ('you are therefore 1 penis'). The aphorism attracted a great deal of attention in Germany precisely because of the absurdity of the behaviour of the authorities themselves. It was the subject of social media memes and inspired street artists. A mural in Hamburg with the same phrase and a call for the minister to resign was painted over for several times by the police, but always restored by the activists. The case of the man who made the original post was closed down in March 2022, citing lack of public interest.

However, a mural in Hamburg using the same message became part of the next hate speech case – posting a photo of it on Facebook landed Augsburg climate activist Alexander Mai in the police's dock as well. In October 2021, he got into an argument on Facebook with Andreas Jurca, a local city councellor from AfD party. In response to Jurca's post, which he considered misogynistic and xenophobic, Mai posted two comments, one of which simply included a photo of the same mural in Hamburg. Around six months later, early one morning, four police officers knocked on the door of Mai's apartment to find out whether he had made the posts and confiscated his computer and phone. Mai had never concealed or denied that he had made the post. While police officers in Germany were usually quick to use force against citizens who opposed Covid restrictions, in this case, the police officers who carried out the hate-speech raid did not even care that both Mai and his flatmate were on a so-called Covid quarantine and ill. Mai's case has not yet been resolved.

Hate speech investigations became common after the migration crisis

The issue of hate speech is also promoted by activist groups in German society, who encourage citizens to report it. One of the groups has even set up a mobile app where it is easy to report observations on “hate speech”.

At the same time, the domestic intelligence agencies in Germany are also engaged in posting hate speech in internet themselves in order to “infiltrate”. They systematically make "hate posts" in various online groups to identify "extremists". Hundreds of such fake accounts are maintained.

But how did Germany get into a situation where police special task forces are measuring people's social media posts with meticulous precision, using a hate speech dashboard, with agents provoking other people to make hateful posts, and police officers then conducting early morning raids on the homes of the posters who share funny pictures on the internet?

Serious engagement with hate speech began during the migration crisis of 2015, when then Chancellor Angela Merkel decided to take in more than a million refugee immigrants and asylum seekers. This caused strong opposition in the country and the harsh protests were also visible online. As noted above, the police began their hate speech raids in 2016, and intensified them significantly in 2019 after the murder of politician Lübcke. The hate speech section of the Penal Code used to be applied primarily against Holocaust-deniers and neo-Nazis who liked to display their love of the swastika, etc., yet its field has now become much broader. The section itself sets out two levels of punishment for hate speech. If it is incitement of hatred directed against a group and it might lead to a public disturbance of peace, it can lead to a prison sentence from three months to five years. However, if it is "simply" disseminating “hate speech” content or making it available to the public, it is punishable by a fine or up to three years of imprisonment.

Effective censorship on social media

Alongside the police work, since 2015, social media companies have been pressured to put in place an effective censorship apparatus. The then Minister of Justice, Heiko Maas, sent a letter to Facebook saying that the internet could not be a lawless space where racist harassment and illegal posting are allowed to flourish. Mr Maas called for stricter intervention and initially social media companies did try to moderate their content more. However, this did not have the desired effect, according to the government, and in 2017 a new law was passed (known as the NetzDG), obliging social media companies to remove "illegal content" within 24 hours. Failure to remove the content risked being fined up to €50 million. Clearly, no company is willing to pay such fines and would thus rather remove all suspicious content immediately – in essence, it has turned into a large-scale censorship.

The law was adopted and came into force at the beginning of 2018, despite being criticised for restricting people’s freedom of expression by a number of human rights organisations and even the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Opinion and Expression, David Kaye, who said it was at odds with international human rights standards

Nonetheless, Germany itself takes the implementation of the law very seriously. For example, in April this year, Twitter was accused of its violation and there was talk of a possible fine.

This kind of online censorship was immediately of interest to others – at least 13 countries seemed inspired by it, including Russia, Belarus, Venezuela, France, the United Kingdom, Australia, India, Kenya, Vietnam, Honduras, Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines. In addition, the European Commission started to develop a general regulation for the European Union, by following the example of the German law.

It needs to be noted, perhaps, that the patterns of state conduct have grown quite similar in the democratic West and the autocratic countries elsewhere, where it concerns one’s freedom of expression. While in the case of the latter societies, we understand it all aimed at the consolidation of power and control over people, do democratic Germany, France, the United Kingdom, or the European Union as a whole, really aim at something else? For what other purpose would such censorship, backed by the power of the police, be desired to be used?