Hate Speech Laws in Europe - A Tool of Thought Control Against Opponents

Sentencing of politicians seems to depend on their worldview: the left is excused.

"Words can be a crime and be punished with whatever punishments the legislators wish." Thomas Hobbes, "Leviathan"

There is a growing tendency among Dutch law enforcement authorities to apply 'hate speech' laws differently to individuals based on their ideological backgrounds. While right-wing politicians often face criminal charges for their public statements or even memes, left-wing individuals are frequently excused for similar behavior

Europe is offering ever more drastic examples of how the hate speech laws are being enforced. Though it is to be acknowledged that risingly acute problems in society and a growing polarisation have led to frustrations that have often come to be expressed rather non-chalantly, the European Union (EU) has forfeited an attempt to understand the problems that are at play and to address them by finding solutions and has instead chosen to react to the consequences – and shut the mouths of the complainers.

What happens though when criticism becomes a crime? What happens when one side is culturally so dominant that the rule of law becomes a means to one’s political ends? Or when hate speech becomes a tool to rule over the minds of one’s political opponents and a means to silence so-called populists? What happens when the state restricts the freedoms of individuals under the guise of defending their well-being? Or when justice becomes selective and law enforcement institutions appear to become guided by an ideology? When the boundaries of crime are so blurred and vague as to depend on the interpretation of the judge who passes the verdict?

The ‘morally good’ progressive ideology

Like all human beings, judges are exposed to all kinds of prejudice. Judges are aware of this, which enables them to avoid or compensate for certain forms of prejudice. However, once morality and ideology come into play, things tend to go awry. Since progressive ideology is now considered the morally sound 'official' doctrine in Western Europe, it is natural that judges will subscribe to it in cases where open standards, human rights, or other vague concepts need to be applied.

In the Netherlands, from 2020 onwards, there has been a growing tendency for people with different ideological views to be treated differently by law enforcement. As Dutch officials have a very high degree of discretion when initiating proceedings, this trend is particularly worrying.

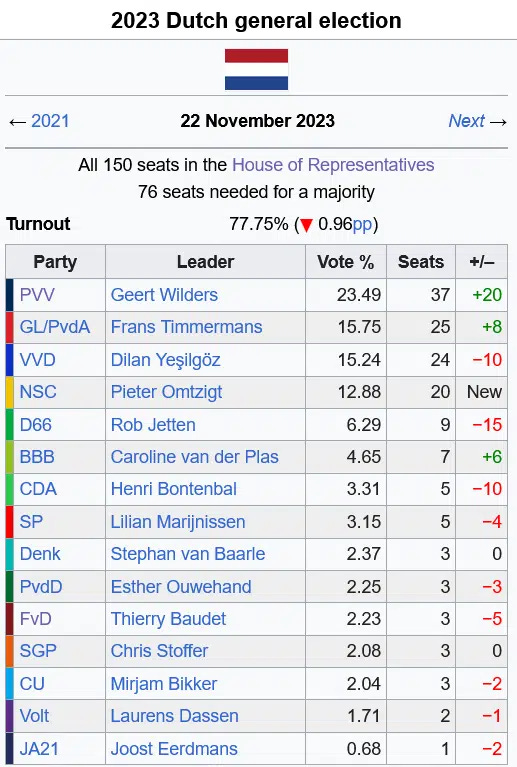

In the Dutch political landscape, the FvD is considered to be a right-wing party – they are referred to in the media as 'radical right', 'extreme right', 'ultra right'. The PVV, the party of Geert Wilders, who won the last elections, is also right-wing on immigration policies, but more left-wing in the field of economics. SGP, JA21, BBB, and BVNL, which are currently no longer represented in the parliament, are also to the right of centre. The CDA is more left of centre and strongly left-leaning are D66, GroenLinks/PvdA (that ran as a joint party in the last elections), Volt, DENK, and PvD.

Polls conducted in 2010 and 2012 show that current or future judges, magistrates (judges who have less power and deal with minor offences), and prosecutors tend to be left-leaning in their political preferences.

Their political preference therefore says a lot about their philosophy of life, which also influences their decisions.

Authorities discriminate between protesters

A deepening trend of differential treatment can be observed in the media from 2020 onwards, when conservatives gradually disappeared from the mainstream media picture, being critical of the official Covid narrative and measures applied. Another worrying trend was the discriminatory approach to protesters. Those protesting against the Covid measures were met with water cannons, truncheons, police horses, and dogs, while Extinction Rebellion protesters blocking the highways were given coffee, and the few punishments meted out to involved individuals were far from being proportionate. It is noteworthy that Winfried Korver, the prosecutor who brought charges against the protesters at the Covid rallies, has himself repeatedly attended Extinction Rebellion rallies, as well as one where some 1,600 demonstrators were detained, yet no one was ever charged. Korver commented, “I am also a person with his own opinion... I support them, for the politicians do nothing to solve the climate issue.“ Such words give cause to doubt the suitability of such a person for his post.

The ‘good’ news in this is that a large number of “coffee drinkers”, i.e. people who gathered to “drink coffee” at these rallies during Covid, despite the general ban on public gatherings, were acquitted in the court. Ironically, however, the ground for their acquittal was that law enforcement had falsified its documents.

Politicians’ freedom of expression in a public debate

Geert Wilders, leader of the right-wing PVV party who won the last elections, is known for his outspokenness and vivid statements. Wilders is seen by some as a far-right extremist because of his decades-long warnings against radical Islam. Many of his pronouncements have been provocative and unconstitutional, such as calling for a ban on the Quran, but in recent years his statements have become more constructive and after winning the election, he has had to make many concessions to be able to form a government, thus earning him the nickname Milder Wilders.

During his political career, Wilders has been the subject of thousands of complaints against his utterances, most of which have not been prosecuted. The first trial concerning Wilders’ statements took place in 2010–2011. The trial concerned statements by Wilders, critical of Muslims, first in the newspaper Volkskrant in 2006-2007 and then in the 2008 documentary Fitna, in which Wilders compared the Quran to Mein Kampf. The charges were initially dismissed since it was felt that “in a social debate and the political arena, freedom of expression should have broader limits”. But as the left-wing activists appealed onwards to the High Court in Amsterdam, a long process of going back and forth between the different levels of the court finally resulted in proceedings being opened for insulting a group of the public and inciting hatred and discrimination. In 2011, Wilders was acquitted, in what the left saw as the death of tolerance and the right as a victory for free speech.

Insulting a group of the public ("groepsbelediging") has existed as a punishable offence in the Netherlands since 1934 and it was originally established to protect the Jews against anti-Semitism that was spreading at the time. Since the 1970s, however, the concept of insulting a group has come to be interpreted more broadly in judicial practice. It has also been debated by some that ‘insulting a group’ is too broad a concept, to begin with, and should be decriminalised.

In 2016, another trial began and on 04.09.2020, the court convicted Geert Wilders of insulting a group of the public, while acquitting him of inciting hatred and discrimination. The decision came into force on 06.07.2021.

On 19.03.2014, Wilders posed a question to the audience at his party’s campaign event as to whether they wanted fewer or more Moroccans in their country. The audience responded “fewer, fewer”, to which Wilders replied, “well, we will arrange it then”. In an interview on 22.03.2014, Wilders explained that he wants the deportation of criminal Moroccans, a halt to Moroccan immigration, and the remigration of Moroccans. The court found that, although Wilders’ statement was made in the context of a political debate, it was, in the court's view, “unnecessarily offensive”. So almost 10 years after the first verdict, the court took the complete opposite view and found that freedom of expression should be limited in the context of a public debate. The court also broadened the definition of “race” by finding that Moroccans are a “race” of their own.

Wilders was found guilty, but not punished, as the court considered that his situation was bad enough in the light of his utterances. Indeed, since November 2004, Wilders is not allowed to go anywhere without a security guard and he resides permanently in a “safe house”.

Is the yardstick the same for everyone?

20.04.2024 was the day of the left-wing GroenLinks/PvdA’s congress, wherein the party leader Frans Timmermans said: “We will not rule out anything in preventing Wilders in coming to power in this country.” Given that Wilders has been the subject of repeated death threats, that a number of individuals have been convicted on these grounds, and that there is a real threat to his life 24/7, it is understandable that such a statement raised questions in Wilders as to what Timmermans meant by ‘anything’ and whether the thought contained the idea of killing him. The prosecution, however, did not see Timmermans’ statement as a crime.

On 04.10.2024, the public prosecutor’s office found two advertisements of the right-wing political party FvD 2023 to be insulting and inciting hatred against a group of the public. One of these clips showed violent acts committed by asylum seekers and immigrants who were opposing the so-called ‘dispersal law’, which means that asylum seekers will have to be settled in different parts all over the Netherlands. In another clip, a non-binary and a trans person were presented, as to draw attention to the indoctrination taking place in society and especially in schools. The non-binary, named Bram, came to prominence when “quite by chance” he took part in a TV programme for young people in 2023, in which Thierry Baudet of the right-wing FvD and Rob Jetten of the left-wing D66 explained their views. The proceedings are ongoing and the FvD leadership is being questioned.

In 2024, the right-wing BBB vice-chair Mona Keijzer was the subject of several appeals for proceedings after she said on the TV show Sophie and Jeroen, on 17.05.2024, that “hatred of Jews is almost part of the Islamic culture”.

The prosecutor’s office found the statement to be an insult to a group of the public and unnecessarily offensive, and though it was noted that Keijzer's statement would in principle be punishable, it was decided to close the proceedings since prosecution would be too much of a restriction on the politician’s freedom of expression. In the case of a so-called ‘crime of expression’, it is always to be kept in mind that pressing charges can discourage others from expressing their opinions and can thus produce a chilling effect in society.

Mr. Keijzer disagreed with the prosecution’s position and considered that the belief that statements are punishable “affects his sincerity, stifles social debate, and thus infringes freedom of expression”. Keijzer still wants the case to be heard by the court and the court to give its opinion. By going to the court, he risks a conviction, but Keijzer believes that if we want to be a free Western society, freedom of expression must not be restricted.

A fascist meme

On 23.09.2022, a photo was posted on the Twitter account of the Ministry of Public Health showing left-wing party ministers Kuipers (D66) and Van Gennip (CDA) raising the SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) flag. A day later, right-wing FvD MP Pepijn van Houweling posted a meme on Twitter with the original photo on the left and the SDG flag replaced by a Nazi flag on the right. The text beside it read, “Facade and reality. SDG.”

Van Houweling responded to the criticism a day later by saying that his aim was not to associate the ministers with the Nazi regime. He deleted the post and posted a new one with a photo of a flag of communist symbols instead of the SDG flag. Van Houweling said the post was intended to warn against the SDGs and Agenda 2030.

On 07.10.2024, the court convicted Van Houweling of inciting intolerance and sentenced him to a suspended fine of €450. The court found that the meme posted by Van Houweling associated the ministers with the Nazi regime and was unnecessarily offensive and that the politician had other options to debate the SDG. The verdict has not yet entered into force.

It is noteworthy that two years earlier, in 2022, a Hague court had ruled that a meme depicting a swastika and replacing Adolf Hitler's head with the head of another person was not a punishable offence.

Similarly, when the NRC newspaper described Van Houweling as a “brownshirt”, the prosecution said the politicians must have a higher threshold of tolerance than others and no proceedings were initiated. For some reason, however, the same approach did not hold with left-wing politicians Kuipers and Van Hennip. In addition, Van Houweling made two unsuccessful allegations against persons who had called him a fascist.

“Clandestine incitement to rebellion”

On 11.06.2024, right-wing MEP Gideon van Meijeren (FvD) was convicted of inciting a riot and sentenced to 200 hours of community service. The conviction consisted of two episodes. The first took place on 02.07.2022 during a farmers’ protest, where Van Meijeren used the phrase “it is not always healthy that the use of violence is a taboo” in his public speech. In the same speech, he said that the pressure on farmers to give up their property was very great and that if they did not do so voluntarily, buses would surely arrive with men in helmets and truncheons, and farmers would be kicked off their land forcibly.

The second episode was a conversation on YouTube in which Van Meijeren said that in a situation where rulers no longer take the will of the people into account, the people should go to the parliament building and not leave until the government has resigned. In the same interview, he spoke of revolutionary movements in history and repeatedly stated that he did not want a violent revolution. The prosecution, however, declared this speech “a dog whistle”, i.e. a subtly directed political message aimed at a specific demographic group, so that it can only be understood by that group, which means that although Van Meijeren said he did not want violence, the court claimed he signalled the opposite. This verdict has not yet entered into force either.

All in all, these hate speech incidents involving Dutch politicians clearly point to a problem that arises with such kind of regulation. As human beings, we are constantly faced with the temptation to silence and punish those who disagree with us – by hating them, insulting them, or blocking them on social media. Dutch legal practice shows clearly that vague or excessive regulations on free speech will lead to their selective application.