In Pursuit of Ultimate Freedom: An Indian Insight into Mechanistic West

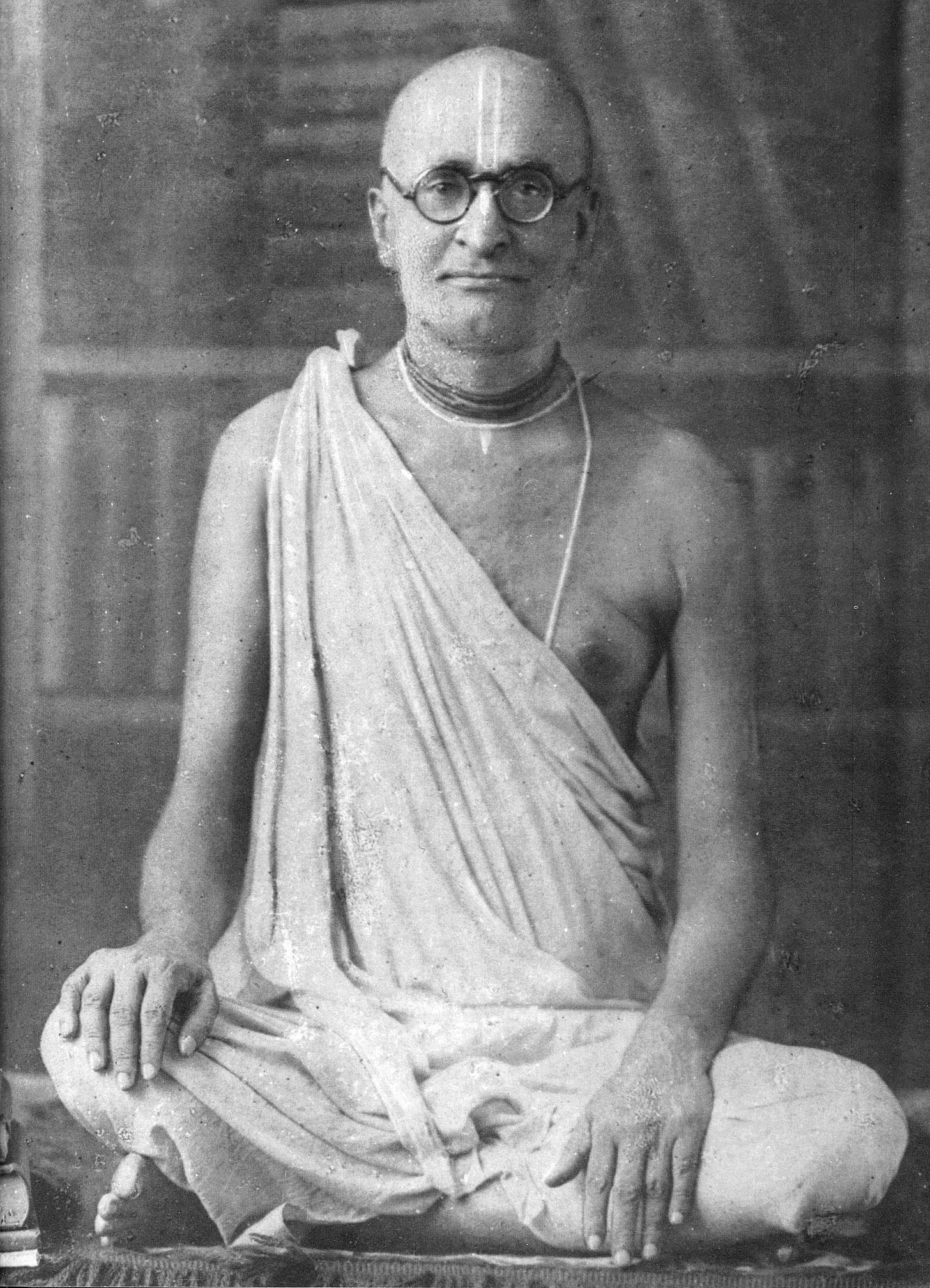

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, "the lion guru" of the early 20th century Bengal, believed that freedom is ultimately found in independence from material circumstances. His ideas have kept their relevance.

Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, born in 1874 as Bimal Prasad Datta, was one of the more formidable philosophers and teachers of the early 20th century Bengal. Known in his time as simha-guru or ‘the lion teacher’, he was famous for his uncompromising criticism of voidism and monism that were popular at the time, opposing them with a personified vision of the Absolute. Although highly critical of institutionalized religion, he saw atheism and monism as main detterents to people’s and society’s self-realization.

It was in 1922 that Sarasvati first met Abhay Charan De, who later became his disciple and a famous proponent of Radha-Krishna worship in the Western world. De, who was later known as A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, was at the time an ardent supporter of Gandhi’s freedom movement and wore its designated khadi (coarse cotton) clothes. De proposed that Indian culture and tradition could never be properly followed or fulfilled until the country remained under British rule. Sarasvati, however, objected to the claim, stating that political freedom was only a secondary matter – the primary concern was personal freedom from the miseries of material existence were caused by ignorance of our finer nature.

Different levels of freedom

Regardless of our affinities, or lack of them, in regards to Sarasvati’s views and affiliations, his statements on the matter seem to reveal something crucial about the notion of freedom in general: it is a highly multidimensional phenomenon. It is true that most of the well-known ‘freedom fighters’ in our history have been the heroes of political struggle. And yet their political fight has often been characterised by a desire for the instatement, or reinstatement of personal freedoms and liberties in the society. The political aim has thus been mostly subservient to the strives and needs of the individual, and the latter should be guarded against the ill-advised infringments of the former, if social and personal freedoms are to prevail.

Our freedoms encompass a vast variety of fields and expressions – not only the freedom to live our life as we choose to, but also the freedom to speak freely, believe freely and if we so desire, to be freely left alone. Freedom is hence not only a matter of physical integrity and protection. Given examples constitute a fabric that has more to do with our self-fulfilment and psychological well-being rather than an immediate material freedom.

Yet freedom as a notion can also be defined as freedom from dependency on the externals, or freedom from the urges of our body and senses – by having mastery of them instead of being dominated by them. And finally, freedom from suffering as such – if not in the form of their absence, then at least by consciousness that can transcend their power. Even if pain and pressure are there, but one will be able to not identify with them. Proposing the chanting of sacred vibrations as the most potent means to achieve that state, this is where Sarasvati believed the freedom of human life ultimately lay.

Mechanistic salvation vs liberation in spirit

While Sarasvati’s claims and aspirations may superficially sound outdated or unintelligible in today’s West, and notions of salvation or spiritual fulfilment feel obsolete to many, it is hard to deny that many of today’s ideological pursuits essentially strive for the same aim. Having seemingly refuted the idea of descending absolution – absolution by grace or as a reward of one’s spiritual surrender or endeavour – the futurist science still seems to seek ways to find eternal life or at least prolongating one’s material existence to new and unseen shapes and lengths. Instead of conquering death by admittance to some form of an afterlife, we are now pursuing to do so by means of improved science and technology.

Similarly, it seems to be salvation that lies at the core of all the more prominent left-wing woke ideologies, inasmuch as they are driven by a belief that an all-encompassing regulation of possible insults and unease and other wrongs will absolve the wrongs of history and lead us to the best available version of a (shall we say ‘perfect’?) society. Harmony, in this view, is only a matter of laying down firmer borders between acceptable and unacceptable, moral and immoral by curbing all of the presumedly hateful speech, calling for absolute concurrence with anyone’s self-determined gender identification, or ceasing to challenge that which authorities instate as scientific and hence true.

In many ways, this seems reflective of how we actually internalize the notion of freedom for ourselves. Even in the world of proclaimed materialism, we are eventually still aspiring for the eternal, or at least as far as possible, a very long life, and we are still aiming for the situation of minimal or no suffering, only in a direct, material sense. One could argue that this speaks something of the nature of freedom we are ultimately striving for. According to Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, however, such an ideal can never be attained by material or mechanistic means, as the body will eventually perish, no matter what we do. Remarkably, he also notes that there will always be some evil in the mundane world, as real purity is attainable only in the realm of one’s consciousness. He says that wherever there is human mind, there exists a principle that can be called evil. “The principle of evil accompanies the principle of good in our worldly life,” he notes in his essay The Genesis of the Principle of Evil, back in 1932. “If there is no evil there cannot be also any earthly good. They are the complementary aspects of an individual function. Those, therefore, who propose to eliminate earthly evil in order to secure unmixed earthly good, engage themselves in a wild goose chase.”[i]

The material world is naturally a realm of dualities – everything that has a beginning, has an end, where there is joy, sorrow will follow. Where there is light, there is bound to be darkness. One cannot exist, or be defined without the other. Where there is ‘a greater good’, there thus has to exist, by definition, ‘a greater evil’. Or one could perhaps even say that the creation of a greater good itself necessitates the simultaneous creation of a greater evil, and if not for anything else, then just for the ‘greater good’ to have something to fight against.

As suggested by many contemporary thinkers – Le Bon, Arendt, Peterson to name a few – any attempt at a mechanistic paradise is always destined to fail, as history has shown us. The duality of this world can never be avoided and denial of its nature ends usually in more suffering, not the other way round. As therefore noted by one of the later followers in Sarasvati’s line, Edward Striker aka Aindra Dasa, “In order to advance, we have to be prepared, ready for revolution – and re-evolution. Real revolution means to change our parameters, to internally evolve, to go beyond our relatively confined conceptions of the way we think things are or should be, to broaden, to elevate our outlook to accommodate a higher dimensional reality. Otherwise, we ourselves become the impediment to our own progress.”

These are goals, and freedoms, that cannot be attained by formal regulation, as they need to grow from within. Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati is one of the examples how past philosophers and instructors may have more to teach us in this regard than many of the highflown slogans of today.

Freedom Research is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

[i] “The Genesis of the Principle of Evil”. The Harmonist, vol. XXX, No.3, pp.73-77. September 1932, Kolkata. https://www.prabhupada-media.net/book-pdf/The_Harmonist_As_It_Is_No_6.pdf

The section where you state,

Where there is ‘a greater good’, there thus has to exist, by definition, ‘a greater evil’. Or one could perhaps even say that the creation of a greater good itself necessitates the simultaneous creation of a greater evil.

Really stood out for me and reminded of Leonard Read who wrote in Why Not try Freedom,

Every individual is faced with the problem of whom to improve,

himself or others. The aim, it seems to me, should be to

effect one's own unfolding, the upgrading of one's own consciousness

- in short, self-perfection. Those who don't even try or, when

trying, find self-perfection too difficult, usually seek to expend

their energy on others. Those who fail to direct their

energy inwardly and let it manifest itself externally - become

immoral leaders. Those who refuse to rule themselves are usually

bent on ruling others. Those who can rule themselves usually

have no interest in ruling others.

And if they locate this source of "greater good" in government - a man-made institution - you have created an authoritarianism you must live with until you revoke it.