Language, Freedom and the Burning Dictionary

Language is a complex system of associations and meanings. By superfluously restricting the way it is used, we will more often than not be stifling the very values these restrictions seek to protect.

Plenty of languages call one’s native talk ‘the mother tongue’. I have often wondered about that expression which seems to suggest that it is not only life that we inherit from our mother or our parents, but also the language that allows us to credit our life with meaning. Yes, we speak the same language that our mother spoke to us and hence it is our ‘mother tongue’ – but wouldn’t it be equally true to reverse the idea and say that language itself is a kind of a mother? It is clear that language is not a mere set of denominations, but functions to create associations and ties between the different phenomena of the world. In Hebrew, רוּחַ can be interpreted both as ‘wind’ and ‘spirit’, suggesting the elusiveness of both, Russian sees ‘stomach’ (живот) stemming from ‘being alive’ (жив), hence setting one’s quality of life in relation to the well-being of one’s gut and stomach, and Finnish links ‘patience’ with ‘suffering’, using the same root for both, ‘kärsivällisyys’ and ‘kärsimys’. Beyond the immediate lexica and grammar, language thus contains an entire world of relations of its own. It is not coincidental then that, biblically, ‘in the beginning was the Word’, or in Indian mythology, according to Bhagavat Purana, all started with the sound of a single word containing the impetus of all creation.

It is important to realize, however, that language is never final. This is the premise of all literature and by extension, all meaning-making in the world. For if all meaning was settled, it would be impossible to strive for new nuances and perspectives in how we reflect the world or envision it, even if we do it in the confines of words that many thousands of people have used before us over hundreds of years. Naturally, the same word can mean different things to different people or take on different hues, reflecting their own experiences and insight, which are hardly ever exactly the same. Else, all further literature, for one, would be pointless. Words are at once universal and personal, and helpful only in as much as they aid our understanding of ourselves and the world.

What does it all mean in today’s ever more divided socio-political landscape? There are clearly those among us who seek to standardize the language, and not only linguistically, but also in its moral qualifications – and hence the rise of various restrictions on the usage of language and the speech law acts. Yet despite their seemingly noble ambitions, it is deeply questionable whether their methods aren’t at odds with the natural laws of language. For any attempt to assign only a single meaning, moreover a single moral meaning, to any particular word is bound to fight language’s inherent quality of being personal and fluid.

What would it mean if, for example, we said that the simple word ‘forest’ can only refer to ‘a boreal forest’, or maybe only to ‘a jungle’ (which is a loan from Hindi’s जंगल, meaning, well, ‘a forest’)? Or vice versa, that terms ‘boreal’ and ‘tropical’ are not inclusive enough and all forest needs to be therefore called, indistinctly, just ‘forest’? I believe this would sound absurd and we would accept as natural that everyone will perceive the notion through their own personal experience and understanding, and meaning something else with it than some other persons is not encroaching on their truth and freedom. What to speak, then, of far more complex matters involving our identity, like language – for instance, one could very well argue that if ‘hate’ can be clearly outlined and standardized into a law, so should its opposite, ‘love’ be. Which would mean our greatest gift can be turned into an ideological construct.

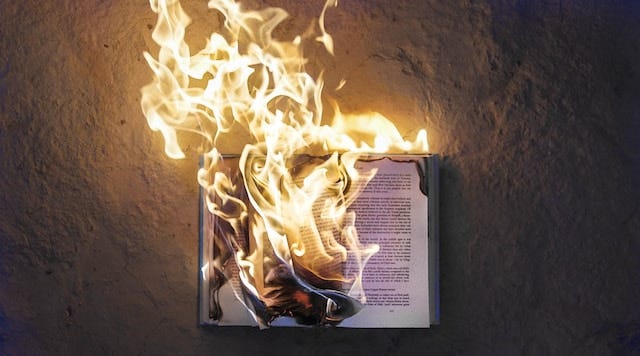

Elif Shafak, a Turkish-British novelist and speaker, has lately wondered, in her wonderful essay How to Stay Sane in an Age of Division, whether the crisis that the Western world is going through isn’t, essentially, ‘a crisis of meaning’. Notably, she has described the present day’s social and political affairs as ‘a dictionary in flames’. The meanings we were used to over the past few decades have seemingly been set on fire and while we are trying to rescue what we can, we must inevitably reinquire about the truth of some of the very basic notions in our culture and society – the meaning of freedom, democracy, identity etc, more so in the post-pandemic world that Shafak’s piece particularly tackles.

When a society is turned into war and division, the language will follow. Words will be mounted as weapons or membership badges, all to be then gleefully thrown at each other – nudged a bit, it will be possible to claim oneself ‘offended’ by virtually anything, from a presumably wrong pronoun to, according to Stanford University’s recent (though by now disengaged from) list of harmful language, calling someone ‘an American’. By standardizing not just language, but meaning as well, one will inevitably legalize some of such weaponry. Journalist Robert Lane Greene has noted already more than a decade ago, and rightfully so, that ‘arguments about language are usually arguments about politics, disguised and channeled through one of our most distinctive markers of identity.’

The more a language is turned into a rigid thing, the more will our world of meanings become rigid, and the possibilities of exploration that any language exists for will be ever more scarce. We’ll be dangerously close to prescribing the way the world needs to be seen, and thus stepping on what is also a personal right of the people. The limits on our freedom of thought seem then no less than an inescapable collateral. As history and experience show, from the slogans of the Soviet Union or those of Communist China, political calls for universal brotherhood or unity can easily turned into mechanisms of exterminating opposition and justifying totalitarian control.[i] In the Soviet regime, for example, to be proud of one’s national heritage and tradition was often only a short step away from being labelled ‘an enemy’, as it was deemed contrary to the ‘universal belonging’. Today, the same kind identity politics are ever more often reflected in the so-called woke ideology where aims of greater inclusiveness are about to end in an actual vanishing of identities, as evident in part of the aforementioned Stanford document. For manipulation of language will hardly ever achieve its proclaimed, desired goals, the opposite is far more likely.

Care, kindness and freedom, and personal respect of everyone, can really thrive only in the realm of personal free thought and meaning, in the voluntary will to explore and embrace them. Instead of further norms on how language may be used, we should look for better ways of personifying the values those norms claim to protect and keep the society open for debate and discussion. Instead of fervently over-regulating language to the point where no-one can presumably be offended anymore, we should know our real wounds and self-worth by learning to stay independent from the encroaching mentality of all-around victimhood which has never really helped us. Let us be reminded – didn’t the seemingly weird characters of Astrid Lindgren and Roald Dahl perhaps teach us more about human kindness and soulfulness eventually than their ‘compassionate’ re-writing ever will, didn’t they trigger our imagination better than any law? To cure the fruit, we’ll need to start at the root. For who is it that can really speak freely? Only they who can think freely, and dream freely, and pursue an understanding of the world as an entirety of relations and ties.

[i] e.g. see Martin, Terry. Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union. Cornell University Press.