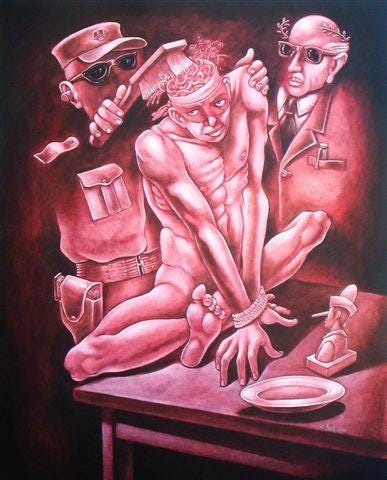

On influencing people, brainwashing and demagogy

People do not understand the basics of manufactured information and allow themselves to be unsuspectingly manipulated.

The use of force against any member of a civilised society against his will can only be justified for one reason - to prevent him from harming others. The physical or moral good of the person himself is not sufficient justification.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, 18591

One of the most fundamental rights of a person is his or her right to individual freedom, because the existence and exercise of other fundamental rights depends on it. Freedom is one of the fundamental rights that has been considered most important in the Western tradition of reasoning and law, and the essence of it is the idea of freedom of thought, speech and action. All the more so that the question of how free, objectively speaking, different individuals really are, is a highly topical one today (at political level).

The problem of freedom is fundamentally a philosophical one - metaphysical and anthropological, moral and social. Yet the history of individual freedom is not as glorious as it is often made out to be. The denial of the ideal of individual freedom was represented by Hegel, Spengler, Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky, who feared that the universal ideal of equality and liberty would destroy both the upper and middle classes, and that human beings would become philistines of an (under)class.

Freedom is freedom to do something and freedom from something. The opposite is inevitability and compulsion. To ensure the sustainable development of the state, it is essential to guarantee the well-being and fundamental rights of the people, while at the same time ensuring fair information. Justice is the most important virtue of social institutions, just as truth is the most important virtue of systems of ideas, writes John Rawls (1921-2002) in his book "The Theory of Justice"2. Justice is also about equality of information, a social good which needs not be determined by a person's position or origin. Rawls stresses that it is the application of a concept of justice to public information that resolves the conflicts that are inevitable for the tensions between people's interests and aspirations, views and attitudes.

In short, from the point of view of social psychology, restricting of person's freedoms is often a classic case of "brainwashing", consisting of any "manipulative" communication or any other set of techniques deliberately aimed at misleading people. In part, it can be equated with demagoguery, which is nothing more than a twisting of the truth, i.e. a system of methods (a method is a known, tried and tested way of achieving a goal) that can be used to conceal the real motives of the actor and the action, to make the means appear to be the ends, to create absurd situations in which the faith and hope of others are lost, love is extinguished, and a sense of certainty is replaced by fear and doubt.

Yet the restriction of individual freedoms, and all the demagoguery that goes along with it, is already common in ancient texts, the knowledge (scientia potentia est) of how to exert influence by word, law or direct force. Since all mass communication of polis-based government was by word of mouth, influence is essentially by communication. However, there is also sometimes talk of the rhetoric of literature, the rhetoric of imagery or even the rhetoric of advertising, film or the media. Independence and freedom have always been under special human scrutiny, even in those systems and for those people who 'brainwash' or negatively influence others on a daily basis.

There have always been many people who would like to understand and know the truth, but those who are able and willing to analyse their own freedom, judgements and choices have been still few throughout the ages. They still remain but few today. The story of George Orwell's "Animal Farm", where the only person who wandered outside the farm to get independent information, was a cat, is illustrative. The cat knew that there was something else outside the farm, and this kept his mind clearer than the others, but he, the cat, did not tell of the fact to the others, but instead remained silent and eventually disappeared - in short, set foot in the free West, where animals were not brainwashed directly.

Psychoanalytical and ideology-based approach to freedom

For a deeper understanding of the psychological and philosophical dialogue between group psychology and the freedom of a individual person, I grabbed hold of Stephen Franzoi's Social Psychology (2008)3 and Sigmund Freud's classic Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse (1921)4 from my bookshelf at home. I wanted to look into the details of the ways in which the classical approaches influence collective group behaviour and our contemporary understandings. I found quite unequivocally that Freud remains an excellent cultural analyst, his notion of group behaviour is increasingly relevant today, especially when linked to Freud's own aforementioned work on mass psychology and ego analysis. The latter work, too, is more relevant than ever because of its educational nature.

Freud's work is a compelling and illuminating introduction to the darker side of collective human behaviour. As the author argues, it is in the group process that the individual loses his or her unique individuality and voluntarily becomes part of ‘a collective soul’ that is always intellectually inferior to the individual's own spiritual level. According to Philip Zimbardo, a classic of empirical social psychology, people in a crowd experience a loss of individuality and undergo deindividuation - a loss of personal identity and a comfortable identification with the mass. What this process signifies is the fact that the individual no longer feels the guilt he once felt in his everyday behaviour and is therefore prepared to act more cruelly or immorally than he did and would as an independent individual.

In the same period as Freud published his work, sociologist Karl Mannheim published his classic work Ideology and Utopia (1929)5 , in which Mannheim explores the concepts of ideology and utopia in the tense climate of political and cultural crisis of the time. Mannheim is interested in the contexts of meanings created by ideology, utopia, which are informational values. According to Mannheim, ideological thought aims at confirming the status quo by creating, in order to maintain it, both collective and communicative fictions that to some extent conceal and distort social reality (political power). In contrast, utopian thinking is powerfully critical of the status quo. A common feature of ideological and utopian exaggeration is a reliance on collective ignorance, i.e. the uneven information of society and different cognitive discourses that result from it. The structures of public power in modern society are largely shaped by policies based on worldviews, where worldviews have become political weapons in the hands of political parties, and where there is in fact no unifying objective worldview. The technologies of political rhetoric are evolving on the basis of social political contradictions. It is in the course of the political struggles that affect the public at large that the existence of collective ignorance is discovered.

In other words, those who are able to take advantage of society's unevenly distributed information and to appeal to people's unconscious urges and motives that shape their behaviour are more successful in persuading society and swaying it in their favour. This is precisely what ideological and utopian discourses aim to do - they do not necessarily associate themselves with what exists in reality, but instead create the most convincing rhetorical fantasies possible in order to achieve some kind of dominance in society. According to Mannheim, this is all the easier to do in a situation that characterises the post-Enlightenment modern man who must continually recreate his equilibrium. Culture and society no longer guarantee external equilibria: society is no longer structured by a stable order based on mythology, religion or tradition. The various conceptions of 'openness' should be mindful of the dangers of falling into similar types of ideological and utopian excesses, through which one or another public institution or political group seeks either to maintain its dominant position or undermine someone's status6.

Another great classic of sociology, Erving Goffman, argued in his work7 that both the individual and collective roles we perform in everyday life become integrated into us over time. Eventually, they become part of our self and our personality as we learn to take each of these roles seriously in our daily lives. It is not surprising that later conceptions of the freedom-group nexus lead back again to the group theory described in Freud's Mass-psychology and the Analysis of the Self. As early as in 1895, Gustave Le Bon8, a classic exponent of historical-worldview psychology (Psychologie der Weltanschauungen), argued that uncontrolled crowds are dangerous, even a pathological phenomena.

Threats from mass behaviour

Most Westerners continue to believe, especially in the case of representative democracy (and in a highly rhetorical and confused legal framework), that social groups (political parties, councils and other collective decision-making bodies) make 'safer and more competent' decisions than individuals. However, numerous research studies in the field of social psychology do not support this view. Group decisions are always much riskier and more immoral than individual ones - even those made after numerous group discussions. As early as in 1979, a researcher of subjective well-being Ed Diener suggested that individuals whose attention is constantly focused on collective decisions or other manifestations of mass behaviour are much less self-aware and self-analysing, and are much more impulsive in their normal behaviour and they are socially less empathetic. Early psychoanalytic conceptions of group behaviour grew out of the mental soil that had developed in the wake of a severe economic crisis in Vienna between 1919 and 1925. This had a devastating economic and psychological impact on individuals.

The Covid-crisis of the last few years is increasingly reminiscent of Sigmund Freud's perpetual laughter at our age and the collective human behaviour that derives from it. It is Freud, and the later analytical psychology based on his ideas, that repeatedly emphasise how collective fear makes people always stupider than they would otherwise be. Crises change both the society and the individual, especially if the individual does not want to be aware of it. In crises, be they personal or collective, the capacity to tolerate uncertainty, which is one of the hallmarks of personal maturity, always plays a role. In both the classical and more recent post-Jungian worldviews, a mature personality has to be aware there are always more conflicting emotions in all of us than we would like to admit - a disturbing ambivalence and indeterminacy about the outside world.

The work of Oxford University neurochemistry researcher Kahtleen Taylor9 clearly demonstrates that there are very few people who are unaffected by informational "brainwashing". One would therefore expect this complex phenomenon to be looked upon favourably, as it is practised by all social systems - some more, some less. Yet, despite the universality of negative influence and demagogy, public opinion does not consider it to be laudable, and it is very difficult to understand this mysterious phenomenon, since we ourselves often fail to perceive the boundaries between our individual freedoms and those of others.

Even worse and more telling is the paradox that the growth of scientific knowledge, the greater availability of general education, has not made people immune to political, rhetorical influence and demagoguery. In noticing and recognising negative influence, demagoguery and outright 'brainwashing', it is not only one's individual life experience (which often comes at a high price) that can help us, but also literature, lectures and a culture of honest debate. There is a large body of academic literature devoted to the study of brainwashing, demagoguery and other manipulative communication phenomena.

What is demagogy?

In ancient, classical philosophy, demagogues were defined only as persons worthy of special honour and trust, and were usually leaders or teachers of the people. Then, as now, no one could call himself a teacher of the people. Nowadays, a demagogue, or 'a brainwasher', is a person or system that is not, or cannot be trusted and who is prepared to turn black into white and act contrary to the truth without a slightest hint of a guilt, if it only serves his or its own purpose. Brainwashing is nowadays defined as a technique of deliberately twisting the truth or objectivity, and a demagogue as a person who has some mastery over the technique and applies it on a daily basis.

Estonian social psychologist Ülo Vooglaid10 stresses that demagogy and the harmful influence of others is mainly a characteristic of unworthy people. It does not really matter whether the motive is self-interest, lust for power, command, anger, stupidity or something else. One might wonder whether the term 'brainwashing' could also be used to describe influence. I think it could, because the only effective way of defeating demagogues may be to know and understand demagoguery and influence well enough to not be fooled by it day in, day out.

Brainwashing, like demagoguery, is a skill, a particularly powerful force in the land of the cowardly and silly people. Those who are poorly educated and whose information field is deficient, who cannot think for themselves, who cannot see or know their own feelings, their own language and their own minds in which meanings are formed, cannot manage themselves independently. People who cannot see connections and dependencies, causes and consequences, who cannot distinguish between their real needs and those of the others, between what is important and what is not, between the part and the whole, cannot really understand their freedom and their possibilities, their limitations and their dangers.

Negative influence on people is possible when people:

do not dare to show that they understand what is being done to them and is attempted to be done to them in the future;

are used to (have been trained from the start) to being manipulated, and would be happy to manipulate other people themselves;

have been "brainwashed" into blindly believing what they are told and what is written, i.e. taking arbitrary texts as truth;

are unable, unable and unwilling to analyse the ideologies and texts being circulated around them; they are fed up and tired, pretending not to care;

also hope to be somehow be a part of the power structure and to be more important as their association with those in power grows;

does not recognise demagogy, demagogues or the consequences of their actions.

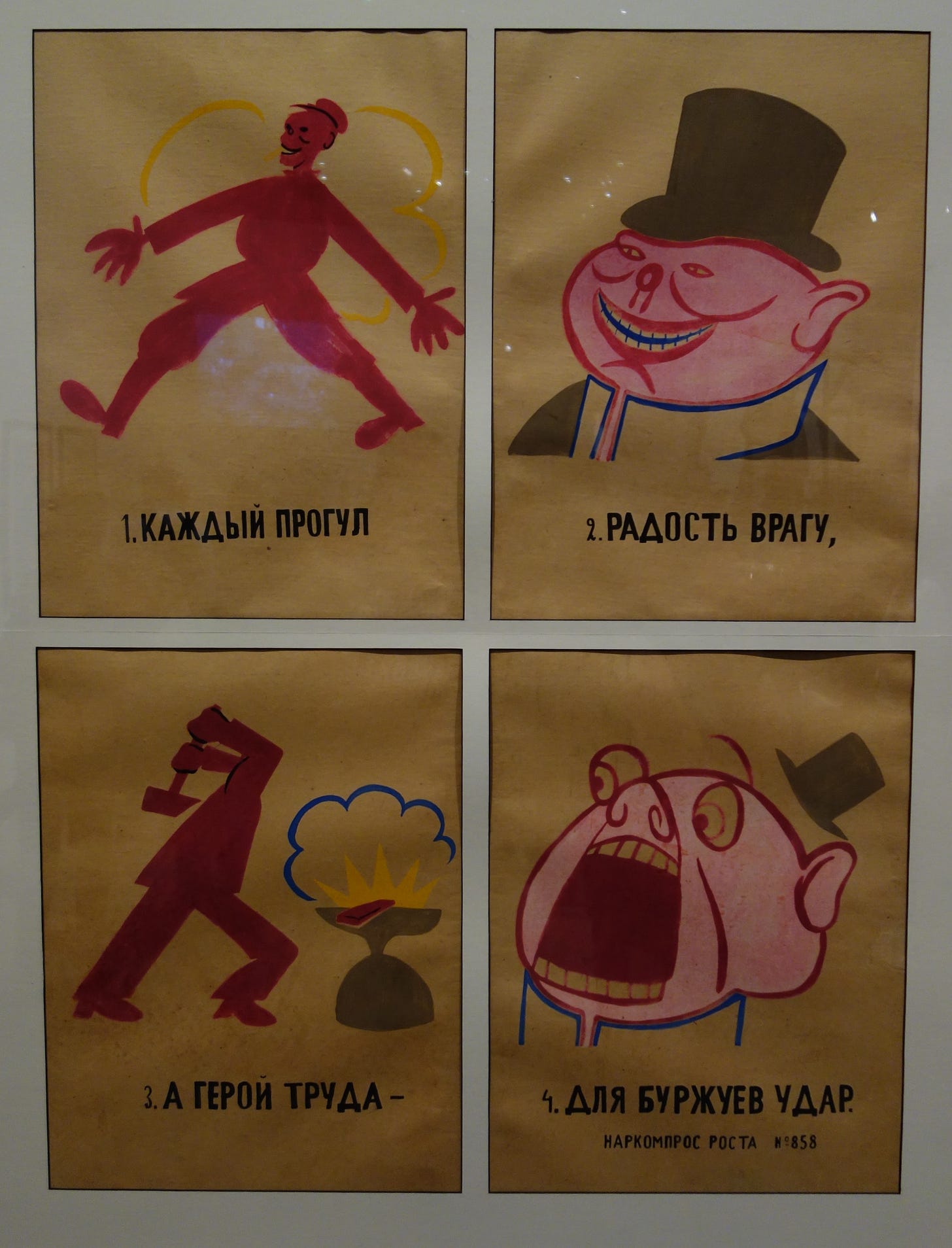

Where does propaganda begin?

The first notable person in the history of propaganda or influence is known to be the philosopher and logician Aristotle (384-322 BC). For him as a thinker, the purpose of persuasion was to convey ideas and points of view, but was not based on diminishing the benefits of others. Aristotle's Rhetoric is a classic and the most famous work on the art of persuasion. It defines persuasion as being based on two pillars: ethos, or the personal qualities of the speaker, and pathos, or the bringing of the audience into an appropriate emotional state. Aristotle stressed ethos most of all, since the concept carries with it the credibility of the speaker. Aristotle argued that perhaps people should pay more attention to the arguments if they do not wish to be influenced by anyone.

Walter Lippmann has been one of the most influential contemporary thinkers in the field of communication and social influence, and one of the founders of public relations as a science. In his work, Lippmann has defined propaganda tools as expedient and purposeful ways of acting and directing to influence people. These instruments can be divided into three categories11:

Cognitive propaganda instruments, which aim to create an image of the object that is suitable for the propagandist by means of signs and symbols (further divided into positive and negative images). Signs and symbols can be words, images, agencies or institutions.

Social propaganda instruments aimed at applying the laws of mass behaviour in order to shape attitudes and behaviour appropriate to the propagandist. To this end, recognised leaders are used, or a group identification is created within the target group on the basis of characteristics appropriate to the propagandist.

Technological propaganda tools aimed at concealing and distorting the facts.

Walter Lippmann was born in New York in 1889. In 1909 he graduated from Harvard University, where he had been an assistant to the highly influential philosopher Georg Santayana. As a young man, Lippmann believed in the socialist approach (he later abandoned it when he realised the great harm this ideology did to individual freedoms and morality), but in his later years he came closer to conservatism and Christian pietism (in the form of the evangelical ethics of Jesus). Lippmann's own thinking and theoretical approach were influenced by the writings of Sigmund Freud, Gustave LeBon, Graham Wallace and John Dewey, which from the outset paid great attention to the influence of individuals and the 'brainwashing' of the masses. Lippmann's approach to public opinion and propaganda was based on the reality of the perceived world. His theory was based on the assumption that people's behaviour is not based on direct and certain knowledge, but on an imaginary image created by or given to them. Thus, if a political and social system succeeds in adapting a person's perception of the world in such a way that the image it creates contributes to the achievement of the influencer's essential goals, it can influence people's thinking and behaviour in the direction that it desires.

The French psychology classic Le Bon argued that we must not forget the fact that it was the power of words that made nations kill each other, and that it is the power of the courts and the media that today settles wars between different interest groups. The first systematic theoretical treatment of propaganda can be found in Walter Lippman's book "Public Opinion", published in 1922.12 According to the definition given in this book, propaganda is an attempt to change the self-image to which people respond, i.e. to replace one social vision by another. The possibility of changing the image is provided by the fact that a man himself cannot grasp and see the world as a whole, as it is extremely dense with information. Lippmann was the first social scientist to conclude that it is the ill-informed and biased, dull subject who behaves according to irrational desires, a fact which makes it possible to influence people and larger groups negatively. Lippmann's psychology of influence and his early approach to brainwashing is based on how people actually perceive the world and act out their behavioral preferences on a daily basis.

Furthermore, Lippman's approach, and his original theory, was based on the assumption that people's behaviour is not based on direct and definite knowledge, but on an image created by or given to them. Thus, at any given moment in time, behaviour and desires are determined by the way in which the subject imagines or allows himself to imagine the world. This is a socio-psychologically important point that the development of propaganda, influence and direct 'brainwashing' in the 21st century is based upon.

The next work of propaganda theory to find wider resonance was Edward Bernays' Propaganda, published in 1928.13 Edward Bernays, also known as ‘the father of public relations’, was born in Vienna in 1891, Sigmund Freud was Bernays' maternal uncle. In addition to Freud, Bernays was influenced by Lippmann, with whom he worked on the U.S. Committee on Public Information during World War I14.

Bernays defines propaganda as a concerted and sustained effort to create or shape events with the aim of influencing public attitudes. Unlike Lippmann, he considered the power of symbols and semiotic communication to be important. Bernays's theory thus placed more importance on symbols than on constructed events in shaping the minds of individuals and groups. Bernays's assessment of the role of public relations in society was consistent15:

"The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, and our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of…. It is they who pull the wires that control the public mind."

It is quite clear that direct and covert brainwashing and propaganda is the ability to change the perceptual objects and images that people respond to. The opportunity to change behaviour is provided by the fact that the human cognitive faculty is not capable of processing the multiplicity of information adequately. What surrounds us must always be studied in part, which would avail us the opportunity to process information more accurately.

Summary

Demagogues and other negative manipulators are able to operate with impunity precisely because people do not understand the basics of information processing and allow themselves to be manipulated unsuspectingly. An overview of 'brainwashing' and demagoguery is essential in improving our understanding of what has happened in the past, as well as understanding people who lived and acted in different times and circumstances, and anticipating future perspectives.

One more fundamental and pragmatic concession should be made: despite the vast amount of research that has been carried out worldwide on the characteristics and detection of demagoguery, political communication and 'brainwashing', it cannot be helped but continuously acknowledged how a successful detection of these phenomena is often difficult, both at human level and at the level of research. Demagoguery and negative influence are dangerous in many respects, but in life and in management, the means of influencing individuals are often necessary, as is particularly evident in the advertising industry.

The only way to counter a stubborn demagogue is often through a more skilful and systematic influence. Since the public is manipulated on a daily basis by demagogic techniques, it is necessary to be constantly aware of this, in other words to read educational and reliable information channels and works. Only the right information will enable us to become more knowledgeable individuals who are freer to make our own decisions.

1 John Stuart Mill. On Liberty. Philosophical Library/Open Road (2015).

2 John Rawls. A Theory of Justice. Harvard University Press; Illustrated edition (2005)

3 Stephen Franzoi. Social Psychology, McGraw-Hill Humanities, Social Sciences; 5th edition (2008).

4 Freud, Sigmund (2005). Mass psychology and ego analysis: the future of an. Fischer Verlag (2005).

5 Karl Mannheim. Ideology and utopia. Klostermann, Vittorio; 8th edition (1995).

6 Joonas Hellermaa. Unmasking the masks: the pretense of beauty and the experience of recognition in Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. Manuscript (2017).

7 Erving Goffman. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh (1956).

8 Gustave Le Bon. The psychology of crowds. Creative Library 11-13, (1991)

9 Kahtleen Taylor. Cruelty: Human Evil and the Human Brain .Oxford University Press; 1st edition (2009). Kahtleen Taylor. Brainwashing: The science of thought control. Oxford University Press; 2nd edition (2017)

10 Ülo Vooglaid. Message to a Citizen. Thinkers handbook (2019)

11 Adu Uudelepp. Propaganda instruments in political television advertisements and modern television commercials (2008).

12 Walter Lippmann. Public opinion. New York: Macmillan, (1947)

13 Edward Bernays. Propaganda. Ig Publishing (2004)

14 https://www.prismjournal.org/uploads/1/2/5/6/125661607/v7-no1-a1.pdf.

15 https://theconversation.com/the-manipulation-of-the-american-mind-edward-bernays-and-the-birth-of-public-relations-44393