“Rulers should be approached like fire”

The ancient wisdom of governance as propounded by Chanakya Pandit – often called India’s Machiavelli – feels telling in today’s turbulent world.

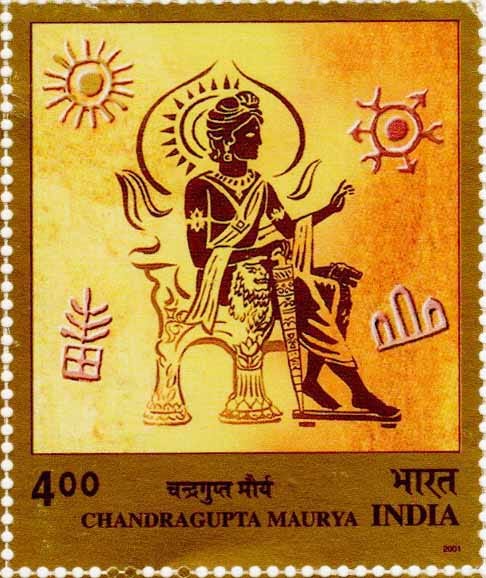

Driving through the affluent and leafy Chanakya Puri, the diplomatic quarter of New Delhi, I am reminded of the personage whose name adorns it –‘the city of Chanakya’ is a reference to one of the best-known and best-esteemed philosophers of India’s ancient past. Chanakya Pandit, at times also referred to as Kautilya, who lived in the 4th and early 3rd century BCE, was an advisor to king Chandragupta Maurya, who is often credited as the first ruler to unite most of India under one administration. The story or, to borrow a term from Indian scriptures, ‘karma’ of Chanakya’s heritage is an interesting one – his two main treatises, Arthashastra (Rules of Benefit) and Raja-niti-shastra (Rules of Royal Conduct, said to be a compilation of notes from other scriptural writings) were lost for centuries, until someone rediscovered them as ancient palm-leaf manuscripts at the Oriental Research Institute in Mysore at the start of the 20th century. Since then, Chanakya’s writings – and both works are extensive affairs – have established themselves firmly in India’s intellectual canon.

Learning from the past: the personage of Chanakya

In the West, Chanakya’s teachings have sometimes been compared to those of Machiavelli, though if that’s fair or accurate feels a contestable matter. After all, the contexts which both wrote their theses vary remarkably and pinning Chanakya’s ideology down merely to statecraft might be a little superficial. There have been others who have seen his role more comparable to that of Aristotle as a teacher to Alexander the Great, viewing Chanakya, like Aristotle, more as a philosopher than a strategist. After all, it is true that both of Chanakya’s above works contain statements and advice on matters ranging from, indeed, political and military strategies and governance down to family dealings and personal affairs. Notably at that, Chanakya never discusses particular wars or stately relations, but talks of principles and perspectives in a far more generalised manner. The beauty of his sutras (maxims) lies oftentimes precisely in the fact that they’re applicable at both personal and societal level. And that is what makes many of them timeless.

Naturally, the world has changed in 2,500 years and one can no doubt find statements in Chanakya’s craft that wouldn’t be looked too kindly upon in 21st century political or social milieu. He approves of gifts (sounding rather like bribes) towards the rulers and he’s not exactly an advocate, to say the least, of laying political power in women’s hands, for example. Yet this doesn’t really substract from the universals of his teachings and judging everything on today’s terms might prove an easy distraction from essence. Henry Kissinger, as one of the later public Western references to Chanakya, in his 2015 book World Order, says Arthashastra is a work that lays out the general requirements of power. I’ve been more attracted, however, by Chanakya’s understanding of, for lack of a better name, ‘the requirements for a successful human life’ as such.

A fair hierarchy of values

There’s a series of Chanakya’s sutras which lay out the basic hierarchy of values necessary for a flourishing society. He says, “Righteousness is the root of happiness. Wealth is the root of righteousness. The state is the root of wealth. Victory over senses is the root of the state. Humility is the root of sense control. Worship of elders is the root of humility. Wisdom results from the worship of elders. And only with wisdom can one prosper.”

Several of these understandings do, of course, refer back to yet earlier teachings from India, for example the juxtaposition of humility and wisdom is rather reminiscent of Bhagavad-gita’s list of knowledge in its 13th chapter (13.8), which begins with humility and pridelessness – not something we would primarily think of as ‘knowledge’ today. Importance is lain also on intergenerational cohesion, of values and respect persisting despite the changing world, which, again, is not unlike Gita’s warning (1.39) how the destruction of family brings about the vanishing of age-old traditions, which in turn would allow irreligion to sprout – though the word for irreligion, adharmaḥ, in the verse could also be interpreted as ‘something unnatural’, i.e. unnatural things would flourish.

The expertise of Chanakya is, however, first and foremost his ability to place these notions in the context of the state. ‘The state is the root of wealth,’ he says, indicating not that all wealth needs to flow from the governance, but rather that in order for wealth to accumulate and be made good use of, a larger general structure needs to be in place to account for conditions of sufficient stability and reliability. It is perhaps because of that he states in his Arthashastra, “In the happiness of the people lies the ruler’s happiness. Their welfare is his welfare.” But also, elsewhere, that, “To be without a master is better than having an arrogant master.”

Though Chanakya does not shy away from cunningness in politics or diplomacy, rather the opposite, there are situations where he advises for it, or advises for secrecy – “To hide one’s flaws, one needs to forgo familiarity,” he says, or “The foolish wish to speak out what was spoken in secret by the master” – his mainstay is that a position of power is, or should be, above all else, a position of service. That this is not always so, Chanakya advises, “A ruler should be approached like fire.” That is, with caution.

Self-control as basis of true governance

One point Chanakya is always rather adamant on, and what is perhaps central to his oeuvre, is the idea that good governance can only spring from the ruler’s self-governance. There are many warnings to addictions and lust as precursors of downfall – of the state and person – and there are calls to be self-contained and – mentally, emotionally – self-sufficient. At the beginning of his Raja-niti-shastra he states the qualifications of a ruler as follows, “The ruler who has controlled his senses, is religious (is dharmātmā – true to the spirit of dharma, his essence, or calling), venerates ascetics, is righteous and interested in the welfare of his subjects is competent to protect his people.”

The topic of self-control as basis of leadership, and freedom, is discussed, of course, in many parts of classical Indian literature and philosophy, both before and after Chanakya. For one, the thought re-emerges in Upadeshamrita of a 16th century philosopher Rupa Gosvami, who had formerly been a minister in the Bengal’s then Muslim government of Nawab Alauddin Husain Shah. Born as a Hindu brahmin, but expelled from the community due to connection with a government of different creed, and then again imprisoned by that rule for desiring to leave the government service, he states what he sees as the universal qualifications of a leader or teacher as follows, “Only a sober-minded person who can tolerate the urge to speak, the mind’s demands, one who doesn’t act upon his anger or the urges of the tongue, belly or genitals, is qualified to take disciples, or lead [teach].”

That Rupa Gosvami forwards speech as foremost among a leader’s qualifications, is well akin to Chanakya’s statements that “there is no greater sin than untruth” or “there is no penance greater than the observance of truth”. Both agree that there is no way to good governance without abstaining from unwarranted or deceitful speech. But also the rest of Gosvami’s verse – written, by the way, originally in the same Sanskrit that Chanakya had used for his writings about 2,000 years earlier – rings close to sutras like “even one with a fourfold army is destroyed if he is a slave of the senses”, or “the lust-ridden ruler cannot perform his duty”, and many others in King Chandragupta’s counsel.

It is perhaps that idea of self-containment or self-governance, more than any other, that feels lost in today’s world and rulership. Continually advertising to want more and obtain more, simplicity and moderation seem far from the top of our hierarchies of social value. If leaders are leading by power, rather than example, and then they will understandably cling more firmly to their position than fair, for their stature and affluence will be dependent just on their rank. It could equally be argued that even our education and culture lays more weight on the results and reactions than actual self-fulfilment. There is hence still plenty in Chanakya’s 2,500 years old teachings that is worthwhile our attention. To lead is, first and foremost, a responsibility and the best leaders would probably be those who are least dependent on their power or have least ambition for it, despite their competence.

The relevance of Chanakya was well summarised also by Rajeev Srinivasan, editor of Firstpost, a decade ago – even though the headline of the piece seems ironically contradictory to the very point made; he says, “The work is astonishingly up-to-date, because human nature hasn’t changed much in a couple of millennia: people like power, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”