The Lost Art of Thankfulness

Today's identity politics have turned into another institution of privileges.

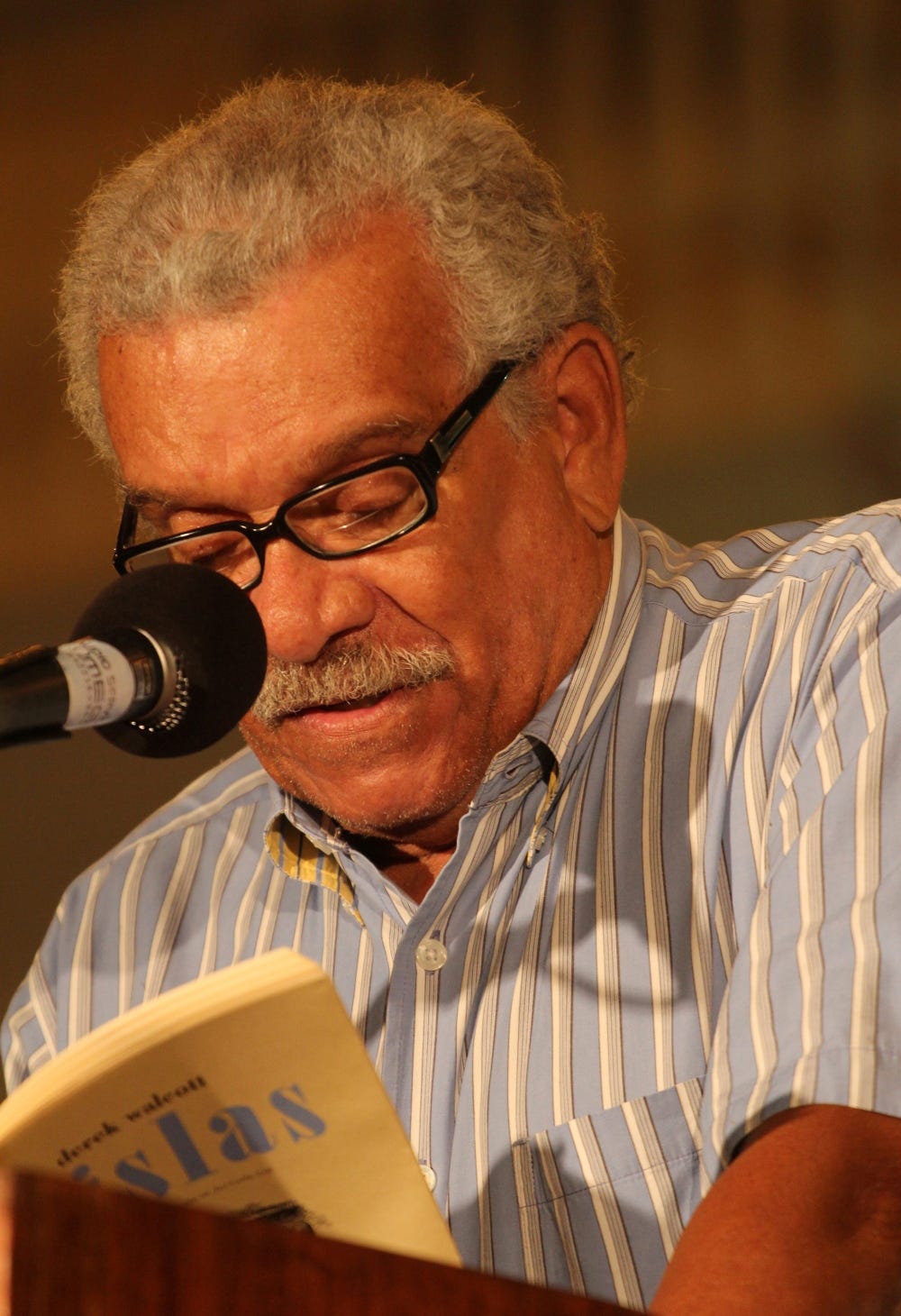

There’s a line in a poem by Derek Walcott that has stuck in my mind: “And I have nothing more to write about than gratitude”. It is from his epic-like piece The Prodigal that came out in 2004, twelve years after he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. However, I believe the line has little to do with his success as an author and is rather more engrained in his relationship with life itself – in the view that life should always be approached in gratitude, being a gift to begin with.

Walcott was born in St Lucia in the Caribbean in 1930, when it was under the British rule. Walcott remained a British citizen and his poetry is abundant not only with references to his native landscape, but also to the European, and particularly the English literary tradition – the language of which he embraced as his own. Although much was made sometimes of his background of being the second black author after Wole Soyinka to win the prime literary award, he himself has openly denounced such attributions, stating, for example, in an interview to Leif Sjöberg already back in 1983, “Race, despite what critics think, has meant nothing to me past early manhood. Race is ridiculous. Even racial war is, at base, humorous. Different colored ants fighting. I have no loyalties to one race more than to another.”

The statement, which could perhaps be called ‘adversarial’ today, was later complemented by an even more principal declaration of his on slavery, in an interview to Robert Brown and Cheryl Johnson at The Cream City Review in 1990, where the laurelled poet stated, “The whole idea of slavery was that you caught people and you sold them to the white man. Black people capturing black people and selling them to the white man. That is the real beginning; that is what should be taught. We have to face that reality. What happened was, one tribe captured the other tribe. That is the history of the world.”

Walcott thus found race to be of secondary importance – it wasn’t race that made someone better or worse as a human being, but one’s disposition and mindset. Evil could lurk, and kindness have its seeds in everyone’s heart. As an author, Walcott found that one was at full liberty to lend from all of his or her heritage, including the colonial past – after all, his own lineage also sprung not only from Africa, but had European roots mixed in. Moreover, he even warned of the restrictive effect of forcing a specific classification on an author – placing the belonging first, e.g. marking someone as a black author, gay author, feminist author etc, one risked confining the writer to an exclusive category and attributing that as the primary value of his or her work. Instead, he thought that identity was better approached without prejudice and emotion, and writes in his poem In Amsterdam how his mother “whose surname was Marlin or Van der Mont took pride in an ancestry she claimed was Dutch”. “Why should I not claim them as fervently,” Walcott writes then of Amsterdam’s chestnuts and tree-shades, of Rubens, Rembrandt etc, “as a creek in the Congo, if her joy was such?”

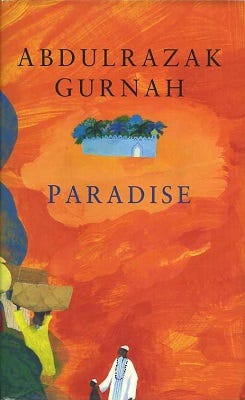

Walcott’s views on slavery and identity seem accepted also in the works of Abdulrazak Gurnah, Tanzanian novelist who is the most recent black author to win the same Nobel Prize in Literature. In his breakthrough novel Paradise, he describes an African society at the onset of European settlements and we can clearly see through the characters of the story that beside the European powers conscripting village folksmen into a war they had no business with, slavery was practiced by Arab merchants and there were violent conflicts between some of the local tribes. Existence of tribal conflict and hatred is evident also in contemporary Africa, for example, in Rwandan genocide of 1994 which claimed something in the range of half a million to one million lives in a little more than three months, with one tribe attacking another in pursuit of ‘ethnic cleansing’. Not far from these two authors is Nigerian-born, Booker-winning Ben Okri, “a world writer” according to his own admission, rather than an outright African or British one, whose novel Starbook, later reworked as The Last Gift of the Master Artists, is a phantasmagoric story of two parallel tribes before the arrival of ‘the white man’ – and showing that it was the internal feud that made the once glorious culture an easy prey for the intruder. “Often the Mamba [a tribal leader] and his followers raided villages, and plundered and pillaged the surrounding countryside,” says Okri, a first-hand witness of the Nigerian civil war in his youth. “[I]t was the Mamba and his followers who attracted the attention of the spies of the white spirits[.]”

This is, of course, not to dismiss the tragedies and traumas of the colonial past, not in Africa, nor anywhere in the world. This is hardly the point of these pre-eminent writers who have also written very sorrowfully on the matter – in fact, Okri’s Starbook is essentially a testament to what was lost to ‘the white winds’. But they seem to beckon us to an understanding of the universals that connect us as human beings, deeper than race or nationality or other such bodily designations.

Today’s wider social discourse seems far more eager to attribute virtue and vice singly, with one group or side often claiming only one or the other of these attributes. One can think of a trans activist cleared of inciting violence when calling for a beating of disagreers at a public rally, or of accusations of racial hatred directed at the man flying a banner of “White Lives Matter”, aside the Black Lives Matter campaign, at an English football club stadium. One can think of a German politician convicted for posting the official statistics of a greatly disproportionate percentage of gang rapes being executed by specific immigrant communities, etc. And in any of such cases, it is hard to see disputes falling the same, would the roles be reversed.

*

Why has the discussion of vice and virtue, good and bad become so insular then? Why do there suddenly seem to be preconditions to claiming a belonging to human tragedy and hurt? After all, in all likelihood, we have all been victims of circumstance or ill will at some point over the course of our lives. There are those among us who have overcome wars or natural disasters, for others the tragedies may have been more private and unspoken. But it is hardly imaginable for anyone to pass through life without ever experiencing an upset. The question is how much we identity ourselves with it.

Losses can be made to surge, made into the defining quality of a person, nation or times. Reversely, they can be brushed off or suppressed or seemingly forgotten. But they can also be employed as a kind of jigsaw pieces, in aid of making sense of our purpose and place in life. A loss can be carried around like a weight in the pocket, yet at times made into a privilege. Or it can be appreciated even its pain and difficulty. Losses are eventually as varied as can be our reactions to them – yet somewhere in there, there is always a choice in how we respond to them or accommodate them.

It is probably fair to say that I’ve had a little more than my share of tribulations and sufferings on my path of life. I struggled with cancer for many of my teenage years, and that wasn’t long after my father had passed away, aged 58. My mother had to support the whole family alone and there were times we struggled to get by. It happened that I was sneered at or left out because of my illness. A stranger even once walked up to me in the street and told me smilingly that she would have thought it preferable to die rather than live in my position. Yet it hardly ever occurred to me to use my situation as an excuse or privilege. It was pretty clear to me quite early on – something that friendships with similarly situated people, e.g. amongst paralympic athletes, have later only corroborated – that would I have done so, I would have only paved myself a way to perdition. There was no one else out there to make me achieve the things I had wanted to achieve in my life.

The hyperliberal obsession to have no-one ever feel offended might sound noble as an idea, but it is by definition destined to result only in ever more aggression. For once someone defines themselves as victims and sets victimhood at the core of their self-description, they are always going to need fresh and ongoing aggression, or else their whole identity would collapse – after all, victimhood presumes the presence of some kind of aggression. More and more views and acts would hence need to be viewed as such, or as insult. Moreover, the blame will always need to be externalised and specified, with responsibility never placed on oneself, but irredeemably on others. Imperfections in oneself will be morally excused for the presumed good intentions, while the same in others can never be forgiven – just so that one can always remain a victim and assure oneself of the role.

That is why the empires’ suggested debt to the great-great-great-(etc)-grandchildren of the historic slave trade can never quite be remunerated, more and more notions need to be seen as hateful, and a certain race, gender or upbringing can be judged as ‘guilty’ by their mere existence. Such a paradigm of victimhood can never really be fulfilled and can only end at last at its own ruin. ‘Racism’ won’t therein be defined as treating everyone unequally, but quite the opposite – treating everyone equally will be seen as racism; ‘inclusion’ will not be defined as an attempt to give everyone a place, but exactly the opposite – it will be viewed as excluding and cancelling those who do not concur with the given view or moral standard. Some of America’s university DEI rubrics, even if good-willingly, are already telling examples of this, e.g. University of California, Berkeley, advising against candidates who express a dislike for race-conscious policies and asking to lower their score if they intend to ‘treat everyone the same’. Presuming to protect those that have previously been downtrodden or vulnerable, the pursuit has, for its unidimensionalism, rather become another institution of privileges.

As the above great authors might suggest, however, this all will eventually run counter to the very nature of life itself and be a poor way to live. By trying rid ourselves of all difficulty and suffering, we will inevitably miss opportunities to grow. By commanding (or even threatening) others never to offend us, we rid ourselves of a chance to become more impervious to others’ opinions and spite, and hence actually more firm in our tolerance. And by defining ourselves by our tragedy and hurt, perhaps in a strange act of presumed martyrdom, we give up a chance to find our real glory and power of transformation. Nothing in nature grows without an effort or struggle – put a seed in the ground and the sprout will need to push itself through the surface, pull from darkness into the light, before it can fulfil its potential to blossom and fruit.

“And I have nothing more to write about than gratitude,” writes Derek Walcott, and later, “There were so many names the rain recited: Alan, Joseph and Claude and Charles and Roddy. The sunlight came through the rain and the drizzle shone as it had done before for everybody.”

We can truly be thankful for only that which we don’t presume, someone told me. Confining ourselves, personally or collectively, to victimhood will inevitably weaken our gratitude for the gifts that life or other people can offer us. It is therefore, I believe, that Walcott also makes the following statement, “The whole idea of oppression is a fallacy, right? If the fallacy is believed, you’re a slave; if it’s not believed, you are not enslaved.” Perhaps it is a way to say that fulfilment will thrive in thankfully accepting responsibility, rather than in laying oneself down as a predetermined victim. Wanting to always be always protected from the outside, we will ultimately make ourselves defenseless. And this will be a detriment to our freedom as well.